This article was originally delivered as a talk to the Young Presidents’ Organization on January 12, 1995, then anthologized in Why Businessmen Need Philosophy: The Capitalist’s Guide to the Ideas Behind Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged” (2011).

“Three seconds remain, the ball is on the one-yard line, here it is — the final play — a touchdown for Dallas! The Cowboys defeat the Jets 24–23!” The crowd roars, the cheering swells. Suddenly, silence.

Everyone remembers that today is the start of a new policy: morality in sports. The policy was conceived at Harvard, championed by the New York Times, and enacted into law by a bipartisan majority in Washington.

The announcer’s voice booms out again: “Today’s game is a big win for New York! Yes, you heard me. It’s wrong for athletes to be obsessed with competition, money, personal gratification. No more dog-eat-dog on the field, no more materialism — no more selfishness! The new law of the game is self-sacrifice: place the other team above yourself, it is better to give than to receive! Dallas therefore loses. As a condition of playing today it had to agree to surrender its victory to the Jets. As we all know, the Jets need a victory badly, and so do their fans. Need is what counts now. Need, not quarterbacking skill; weakness, not strength; help to the unfortunate, not rewards to the already powerful.”

Nobody boos — it certainly sounds like what you hear in church — but nobody cheers, either. “Football will never be the same,” mutters a man to his son. The two look down at the ground and shrug. “What’s wrong with the world?” the boy asks.

The basic idea of this fantasy, the idea that self-sacrifice is the essence of virtue, is no fantasy. It is all around us, though not yet in football. Nobody defends selfishness any more: not conservatives, not liberals; not religious people, not atheists; not Republicans, not Democrats.

White males, for instance, should not be so “greedy,” we hear regularly; they should sacrifice more for women and the minorities. Both employers and employees are callous, we hear; they spend their energy worrying about their own futures, trying to become even richer, when they should be concerned with serving their customers. Americans are far too affluent, we hear; they should be transferring some of their abundance to the poor, both at home and abroad.

If a poor man finds a job and rises to the level of buying his own health insurance, for instance, that is not a moral achievement, we are told; he is being selfish, merely looking out for his own or his family’s welfare. But if the same man receives his health care free from Washington, using a credit card or a law made by Bill Clinton, that is idealistic and noble. Why? Because sacrifice is involved: sacrifice extorted from employers, by the employers’ mandate, and from doctors through a noose of new regulations around their necks.

If America fights a war in which we have a national interest, such as oil in the Persian Gulf, we hear that the war is wrong because it is selfish. But if we invade some foreign pesthole for no selfish reason, with no national interest involved, as in Bosnia, Somalia or Haiti, we hear praise from the intellectuals. Why? Because we are being selfless.

The Declaration of Independence states that all men have an inalienable right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” What does the “pursuit of happiness” mean? Jefferson does not say that you have a duty to pursue your neighbor’s pleasure or the collective American well-being, let alone the aspirations of the Bosnians. He upholds a selfish principle: each man has right to live for his own sake, his own personal interests, his happiness. He does not say: run roughshod over others, or: violate their rights. But he does say: pursue your own goals independently, by your own work, and respect every other individual’s right to do the same for himself.

In essence, America was conceived by egoists. The Founding Fathers envisioned a land of selfishness and profit-seeking — a nation of the self-made man, the individual, the ego, the “I.” Today, however, we hear the opposite ideas everywhere.

Who are the greatest victims of today’s attitude? Who are the most denounced and vilified men in the country? You are — you, the businessmen. And the bigger and better you are, the worse you are morally, according to today’s consensus. You are denounced for one sin: you are the epitome of selfishness.

In fact, you really are selfish. You are selfish in the noblest sense, which is inherent in the very nature of business: you seek to make a profit, the greatest profit possible — by selling at the highest price the market will bear while buying at the lowest price. You seek to make money — gigantic amounts of it, the more better — in small part to spend on personal luxury, but largely to put back into your business, so that it will grow still further and make even greater profits.

As a businessman, you make your profit by being the best you can be in your work, i.e., by creating goods or services that your customers want. You profit not by fraud or robbery, but by producing wealth and trading with others. You do benefit other people, or the so-called “community,” but this is a secondary consequence of your action. It is not and cannot be your primary focus or motive.

The great businessman is like a great musician, or a great man in any field. The composer focuses on creating his music; his goal is to express his ideas in musical form, the particular form which most gratifies and fulfills him himself. If the audience enjoys his concerto, of course he is happy — there is no clash between him and his listeners — but his listeners are not his primary concern. His life is the exercise of his creative power to achieve his own selfish satisfaction. He could not function or compose otherwise. If he were not moved by a powerful, personal, selfish passion, he could not wring out of himself the necessary energy, effort, time and labor; he could not endure the daily frustrations of the creative process. This is true of every creative man. It is also true of you in business, to the extent that you are great, i.e., to the extent that you are creative in organization, management, long-range planning, and their result: production.

Business to a creative man is his life. His life is not the social results of the work, but the work itself, the actual job — the thought, the blueprints, the decisions, the deals, the action. Creativity is inherently selfish; productivity is inherently selfish.

The opposite of selfishness is altruism. Altruism does not mean kindness to others, nor respect for their rights, both of which are perfectly possible to selfish men, and indeed widespread among them. Altruism is a term coined by the nineteenth-century French philosopher Auguste Comte, who based it on the Latin “alter,” meaning “other.” Literally, the term means: “other-ism.” By Comte’s definition and ever since, it means: “placing others above oneself as the basic rule of life.” This means not helping another out occasionally, if he deserves it and you can afford it, but living for others unconditionally — living and, above all, sacrificing for them; sacrificing your own interests, your pleasures, your own values.

What would happen to a business if it were actually run by an altruist? Such a person knows nothing about creativity or its requirements. What his creed tells him is only: “Give up. Give up and give away; give away to and for others.” What should he give away? Whatever is there; whatever he has access to; whatever somebody else has created.

Either a man cares about the process of production, or he does not. If he cares about the process, it must be his primary concern; not the beneficiaries of the process, but the personal fulfillment inherent in his own productive activity. If he does not care about it, then he cannot produce.

If the welfare of others were your primary aim, then you would have to dismantle your business. For instance, you would have to hire needy workers, regardless of their competence — whether or not they lead you to a profit. Why do you care about profit, anyway? As an altruist, you seek to sacrifice yourself and your business, and these workers need the jobs. Further, why charge customers the highest price you can get — isn’t that selfish? What if your customers need the product desperately? Why not simply give away goods and services as they are needed? An altruist running a business like a social work project would be a destroyer — but not for long, since he would soon go broke. Do you see Albert Schweitzer running General Motors? Would you have prospered with Mother Teresa as the CEO of your company?

Many businessmen recognize that they are selfish, but feel guilty about it and try to appease their critics. These businessmen, in their speeches and advertisements, regularly proclaim that they are really selfless, that their only concern is the welfare of their workers, their customers, and their stockholders, especially the widows and orphans among them. Their own profit, they say, is really not very big, and next year, they promise, they will give even more of it away. No one believes any of this, and these businessmen look like nothing but what they are: hypocrites. One way or another, everyone knows that these men are denying the essence and purpose of their work. This kind of PR destroys any positive image of business in the public mind. If you yourselves, by your own appeasement, damn your real motives and activity, why should anyone else evaluate you differently?

Some of you may reply: “But I really am an altruist. I do live for a higher purpose. I don’t care excessively about myself or even my family. I really want primarily to serve the needy.” This is a possible human motive — it is a shameful motive, but a possible one. If it is your motive, however, you will not be a successful businessman, not for long. Why is it shameful? Let me answer by asking the altruists among you: Why do you have such low self-esteem? Why don’t you and those you love deserve to be the beneficiaries of your efforts? Are you excluded from the Declaration of Independence merely because you are a businessman? Does a producer have no right to happiness? Does success turn you into a slave?

You do not expect your workers to say, “We don’t care about ourselves; we’re only servants of the public and of our bosses.” In fact, labor says the exact opposite. Your workers stand up proudly and say, “We work hard for a living. We deserve a reward, and we damn well expect to get it!” Observe that the country respects such workers and their attitude. Why then are businessmen supposed to be serfs? Aren’t you as good as the rest of mankind? Why should you alone spend your precious time sweating selflessly for a reward that is to be given to someone else?

The best among you do not believe the altruist mumbo-jumbo. You have, however, long been disarmed by it. Because you are the victim of a crucial power, against which you are helpless. That power is philosophy.

This brings us to the question of why businessmen need philosophy.

The issue with which we began — selfishness vs. altruism — is a philosophic issue; specifically, it is a moral or ethical issue. One of the important questions of ethics is: should a man live for himself, or should he sacrifice for something beyond himself? In the medieval era, for example, philosophers held that selfishness was wicked, that men must sacrifice themselves for God. In such an era, there was no possibility of an institutionalized system of profit-seeking companies. To the medievals, business would represent sheer wickedness.

This philosophy gradually changed, across centuries, culminating in the view of Jefferson, who championed the selfish pursuit of one’s own happiness. He took this idea from John Locke, who got it, ultimately, from Aristotle, the real father of selfishness in ethics. Jefferson’s defense of the right to happiness made possible the founding of America and of a capitalist system. Since the eighteenth century, however, the philosophic pendulum has swung all the way back to the medieval period. Today, once again, self-sacrifice is extolled as the moral ideal.

Why should you care about this philosophic history? As a practical man, you must care; because it is an issue of life and death. It is a simple syllogism. Premise one: Businessmen are selfish; which everyone knows, whatever denials or protestations they hear. Premise two: Selfishness is wicked; which almost everyone today, including the appeasers among you, thinks is self-evident. The inescapable conclusion: Businessmen are wicked. If so, you are the perfect scapegoats for intellectuals of every kind to blame for every evil or injustice that occurs, whether real or trumped up.

If you think that this is merely theory, look at reality — at today’s culture — and observe what the country thinks of business these days. Popular movies provide a good indication. Do not bother with such obviously left-wing movies as Wall Street, the product of avowed radicals and business-haters. Consider rather the highly popular Tim Allen movie The Santa Clause. It was a simple children’s fantasy about Santa delivering gifts; it was seasonal family trivia that upheld no abstract ideas or philosophy, the kind of movie which expressed only safe, non-controversial, self-evident sentiments. In the middle of the movie, with no plot purpose of any kind, the story leaves Santa to show two “real businessmen”: toy manufacturers scheming gleefully to swindle the country’s children with inferior products (allegedly, to make greater profits thereby). After which, the characters vanish, never to be seen again. It was a sheer throwaway — and the audience snickers along with it approvingly, as though there is no controversy here. “Everybody knows that’s the way businessmen are.”

Imagine the national outcry if any other minority — and you a very small minority — were treated like this. If a “quickie” scene were inserted into a movie to show that females are swindlers, or gays, or blacks — the movie would be denounced, reedited, sanitized, apologized for and pulled from the theaters. But businessmen? Money-makers and profit-seekers? In regard to them, anything goes, because they are wicked, i.e., selfish. They are “pigs,” “robbers,” “villains” — everyone knows that! Incidentally, to my knowledge, not one businessman or group of them protested against this movie.

There are hundreds of such movies, and many more books, TV shows, sermons and college lectures, all expressing the same ideas. Are such ideas merely talk, with no practical consequences for you and your balance sheets? The principal consequence is this: once you are deprived of moral standing, you are fair game. No matter what you do or how properly you act, you will be accused of the most outrageous evils. Whether the charges are true or false is irrelevant. If you are fundamentally evil, as the public has been taught to think, then any accusation against you is plausible — you are, people think, capable of anything.

If so, the politicians can then step in. They can blame you for anything, and pass laws to hogtie and expropriate you. After all, everyone feels, you must have obtained your money dishonestly; you are in business! The antitrust laws are an eloquent illustration of this process at work. If some official in Washington decides that your prices are “too high,” for instance, it must be due to your being a “monopolist”: your business, therefore, must be broken up, and you should be fined or jailed. Or, if the official feels that your prices are “too low,” you are probably an example of “cutthroat competition,” and deserve to be punished. Or, if you try to avoid both these paths by setting a common price with your competitors — neither too high or too low, but just right — that is “conspiracy.” Whatever you do, you are guilty.

Whatever happens anywhere today is your fault and guilt. Some critics point to the homeless and blame their poverty on greedy private businessmen who exploit the public. Others, such as John Kenneth Galbraith, say that Americans are too affluent and too materialistic, and blame greedy private businessmen, who corrupt the masses by showering them with ads and goods. Ecologists claim that our resources are vanishing and blame it on businessmen, who squander natural resources for selfish profit. If a broker dares to take any financial advantage from a lifetime of study and contacts in his field, he is guilty of “insider trading.” If racial discrimination is a problem, businessmen must pay for it by hiring minority workers, whether qualified or not. If sexual harassment is a problem, businessmen are the villains; they must be fondling their downtrodden filing clerks, as they leave for the bank to swindle the poor widows and orphans. The litany is unmistakable: if anybody has any trouble of any kind, blame the businessman — even if a customer spills a cup of her coffee miles away from the seller’s establishment. By definition, businessmen have unlimited liability. They are guilty of every conceivable crime because they are guilty of the worst, lowest crime: selfishness.

The result is an endless stream of political repercussions: laws, more controls, more regulations, more alleged crimes, more fines, more lawsuits, more bureaus, more taxes, more need to bow down on your knees before Washington, Albany or Giuliani, begging for favors, merely to survive. All of this means: the methodical and progressive enslavement of business.

No other group in the world would stand for or put up with such injustice — not plumbers or philosophers, not even Bosnians or Chechens. Any other group, in outrage, would assert its rights — real or alleged — and demand justice. Businessmen, however, do not. They are disarmed because they know that the charge of selfishness is true.

Instead of taking pride in your selfish motives and fighting back, you are ashamed, undercut and silent. This is what philosophy — bad philosophy — and specifically a bad code of morality has done to you. Just as such a code would destroy football, so now it is destroying the United States.

Today, there is a vicious double standard in the American justice system. Compare the treatment of accused criminals with that of accused businessmen. For example: if a man (like O.J. Simpson) commits a heinous double-murder, mobs everywhere chant that he is innocent until proven guilty. Millions rush to his defense, he buys half the legal profession and is acquitted of his crimes. Whereas, if a businessman invents a brilliant method of financing business ventures through so-called junk bonds, thereby becoming a meteoric success while violating not one man’s rights, he is guilty — guilty by definition, guilty of being a businessman — and he must pay multi million-dollar fines, perform years of community service, stop working in his chosen profession, and even spend many years in jail.

If, in the course of pursuing your selfish profits, you really did injure the public, then the attacks on you would have some justification. But the opposite is true. You make your profits by production and you trade freely with your customers, thereby showering wealth and benefits on everyone. (I refer here to businessmen who stand on their own and actually produce in a free market, not those who feed at the public trough for subsidies, bailouts, tariffs and government-dispensed monopolies.)

Now consider the essential nature of running a business and the qualities of character it requires.

There is an important division of labor not taught in our colleges. Scientists discover the laws of nature. Engineers and inventors apply those laws to develop ideas for new products. Laborers will work to produce these goods if they are given a salary and a prescribed task, i.e., a plan of action and a productive purpose to guide their work. These people and professions are crucial to an economy. But they are not enough. If all we had was scientific knowledge, untried ideas for new products, and directionless physical labor, we would starve.

The indispensable element here — the crucial “spark plug,” which ignites the best of every other group, transforming merely potential wealth into the abundance of a modern industrial society — is business.

Businessmen accumulate capital through production and savings. They decide in which future products to invest their savings. They have the crucial task of integrating natural resources, human discoveries and physical labor. They must organize, finance and manage the productive process, or choose, train and oversee the men competent to do it. These are the demanding, risk-laden decisions and actions on which abundance and prosperity depend. Profit represents success in regard to these decisions and actions. Loss represents failure. Philosophically, therefore, profit is a payment earned by moral virtue — by the highest moral virtue. It is payment for the thought, the initiative, the long-range vision, the courage and the efficacy of the economy’s prime movers: the businessmen.

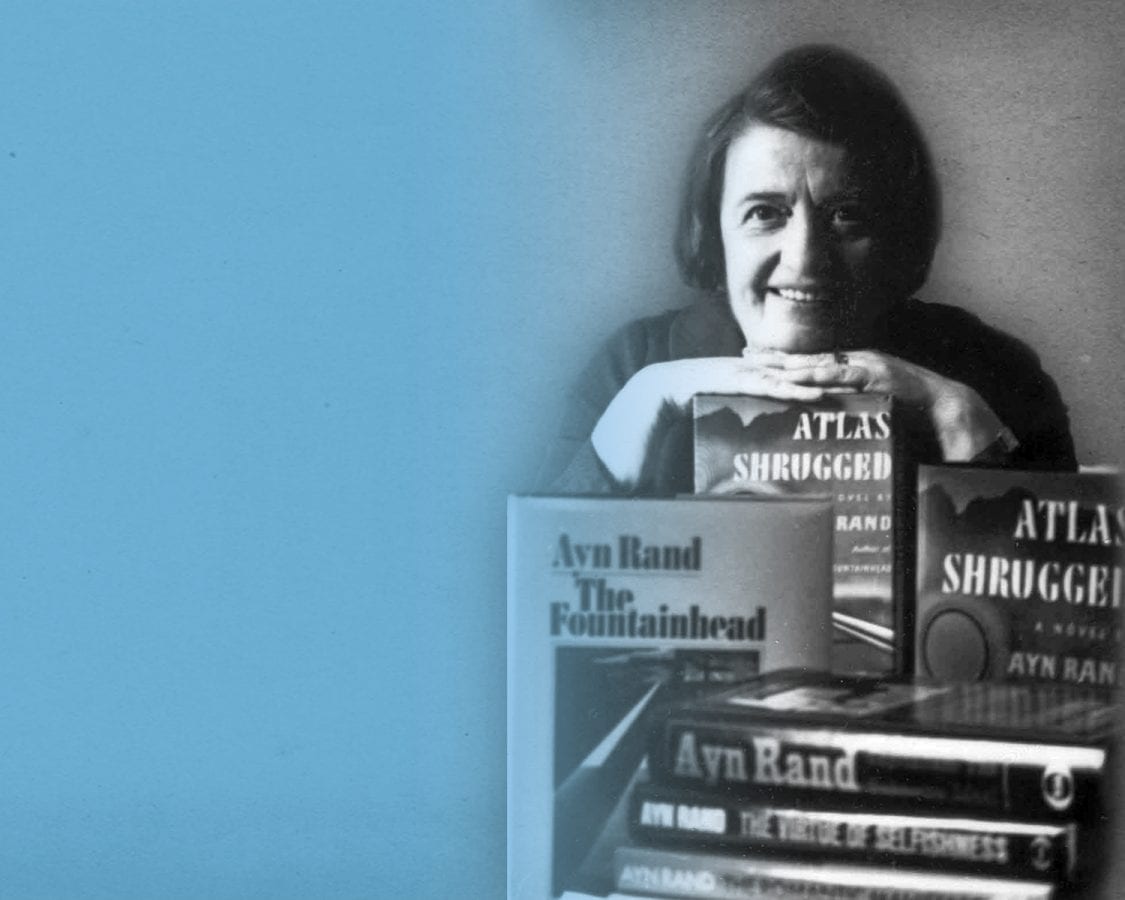

Your virtue confers blessings on every part of society. By creating mass markets, you make new products available to every income level. By organizing productive enterprises, you create employment for men in countless fields. By using machines, you increase the productivity of labor, thus raising the workingman’s pay and rewards. The businessman, to quote Ayn Rand,

is the great liberator who, in the short span of a century and a half, has released men from bondage to their physical needs, has released them from the terrible drudgery of an eighteen-hour workday of manual labor for their barest subsistence, has released them from famines, from pestilences, from the stagnant hopelessness and terror in which most of mankind had lived in all the pre-capitalist centuries — and in which most of it still lives, in non-capitalist countries. 1 Ayn Rand, For the New Intellectual (New York: New American Library, 1961), p. 27.

If businessmen are such great liberators, you can be sure that those who denounce you know this fact. The truth is that you are denounced partly because you are mankind’s great providers and liberators, which raises another critical topic.

Selfishness is not the only virtue for which you are damned by today’s intellectuals. They invoke two other philosophical issues as a club to condemn you with: reality and reason.

By “reality,” I mean the universe around us; the material world in which we live and which we observe with our senses: the earth, the planets, the galaxies. As businessmen you are committed to this world, not to any other dimension alleged to transcend it. You are not in business to secure or offer supernatural rewards, other-worldly bliss or the welfare of an ecological rose garden in the twenty-fifth century. You pursue real, this-worldly values, here and now. You produce physical goods and tangible services. You seek monetary profit, which you intend to invest or spend now. You do not offer your customers out-of-body experiences, UFO rides or reincarnation as Shirley MacLaine. You offer real, earthly pleasures; you make possible physical products, rational services and the actual enjoyment of this life.

This completely contradicts many major philosophical schools. It puts you into conflict with every type of supernaturalist, from the medieval-style theists on through today’s “New Age” spiritualists and mystics. All these people like to demean this life and this world in favor of another, undefined existence in the beyond: to be found in heaven, in nirvana or on LSD. Whatever they call it, this other realm is beyond the reach of science and logic.

If these supernaturalists are right, then your priorities as businessmen — your philosophic priorities — are dead wrong. If the material world is, as they claim, “low, vulgar, crude, unreal,” then so are you who cater to it. You are materialistic animals devoted to inferior physical concerns. By showering men with material values, you are corrupting and debasing them, as Galbraith says, rather than truly liberating them.

A businessman must be worldly and concerned with the physical. From the physical laws ruling your assembly line to the cold, hard facts of your financial accounts, business is a materialistic enterprise. This is another reason why there could be no such thing as business in the medieval era: not only selfishness, but worldliness, was considered a major sin. This same combination of charges — selfishness and materialism — is unleashed against you today by the modern equivalent of the medieval mentality. The conclusion they reach is the same: “Down with business!

The third philosophic issue is the validity of reason. Reason is the human faculty which forms concepts by a process of logic based on the evidence of the senses; reason is our means of gaining knowledge of this world and guiding our actions in it. By the nature of their field, businessmen must be committed to reason, at least in their professional lives. You do not make business decisions by consulting tea leaves, the “Psychic Friends Network,” the Book of Genesis, or any other kind of mystic revelation. If you tried to do it, then like all gamblers who bet on blind intuition, you would be ruined.

Successful businessmen have to be men of the intellect. Many people believe that wealth is a product of purely physical factors, such as natural resources and physical labor. But both of these have been abundant throughout history and are in poverty-stricken nations still today, such as India, Russia and throughout Africa.

Wealth is primarily a product not of physical factors, but of the human mind — of the intellectual faculty — of the rational, thinking faculty. I mean here the mind not only of scientists and engineers, but also the mind of those men and women — the businessmen — who organize knowledge and resources into industrial enterprises.

Primarily, it is the reason and intelligence of great industrialists that make possible electric generators, computers, coronary-bypass surgical instruments and spaceships.

If you are to succeed in business, you must make decisions using logic. You must deal with objective realities — like them or not. Your life is filled with numbers, balance sheets, cold efficiency and rational organization. You have to make sense — to your employees, to your customers, and to yourself. You cannot run a business as a gambler plays the horses, or as a cipher wailing, “Who am I to know? My mind is helpless. I need a message from God, Nancy Reagan’s astrologer or Eleanor Roosevelt’s soul.” You have to think.

The advocates of a supernatural realm never try to prove its existence by reason. They claim that they have a means of knowledge superior to reason, such as intuition, hunch, faith, subjective feeling or the “seat of their pants.” Reason is their enemy, because it is the tool that will expose their racket: so they condemn it and its advocates as cold, analytic, unfeeling, straight-jacketed, narrow, limited. By their standard, anyone devoted to reason and logic is a low mentality, fit only to be ruled by those with superior mystic insight. This argument originated with Plato in the ancient world, and it is still going strong today. It is another crucial element in the anti-business philosophy.

To summarize, there are three fundamental questions central to any philosophy, which every person has to answer in some way: What is there? How do you know it? And, what should you do?

The Founding Fathers had answers to these questions. What is there? “This world,” they answered, “nature.” (Although they believed in God, it was a pale deist shadow of the medieval period. For the Founding Fathers, God was a mere bystander, who had set the world in motion but no longer interfered.) How did they know? Reason was “the only oracle of man,” they said. What should you do? “Pursue your own happiness,” said Jefferson. The result of these answers — i.e., of their total philosophy — was capitalism, freedom and individual rights. This brought about a century of international peace, and the rise of the business mentality, leading to the magnificent growth of industry and of prosperity.

For two centuries since, the enemies of the Founding Fathers have given the exact opposite answers to these three questions. What is there? “Another reality,” they say. How do they know? “On faith.” What should you do? “Sacrifice yourself for society.” This is the basic philosophy of our culture, and it is responsible for the accelerating collapse of capitalism, and all of its symptoms: runaway government trampling on individual rights, growing economic dislocations, worldwide tribal warfare and international terrorism — with business under constant, systematic attack.

Such is the philosophic choice you have to make. Such are the issues on which you will ultimately succeed or fail. If the anti-business philosophy with its three central ideas continues to dominate this country and to spread, then businessmen as such will become extinct, as they were in the Middle Ages and in Soviet Russia. They will be replaced by church authorities or government commissars. Your only hope for survival is to fight this philosophy by embracing a rational, worldly, selfish alternative.

We are all trained by today’s colleges never to take a firm stand on any subject: to be pragmatists, ready to compromise with anyone on anything. Philosophy and morality, however, do not work by compromise. Just as a healthy body cannot compromise with poison, so too a good man cannot compromise with evil ideas. In such a set up, an evil philosophy, like poison, always wins. The good can win only by being consistent. If it is not, then the evil is given the means to win every time.

For example, if a burglar breaks into your house and demands your silverware, you have two possible courses of action. You might take a militant attitude: shoot him or at least call the police. That is certainly uncompromising. You have taken the view, “What’s mine is mine, and there is no bargaining about it.” Or, you might “negotiate” with him, try to be conciliatory, and persuade him to take only half your silverware. Whereupon you relax, pleased with your seemingly successful compromise, until he returns next week demanding the rest of your silverware — and your money, your car and your wife. Because you have agreed that his arbitrary, unjust demand gives him a right to some of your property, the only negotiable question thereafter is: how much? Sooner or later he will take everything. You compromised; he won.

The same principle applies if the government seeks to expropriate you or regulate your property. If the government floats a trial balloon to the effect that it will confiscate or control all industrial property over $10 million in the name of the public good, you have two possible methods of fighting back. You might stand on principle — in this case, the principle of private property and individual rights — and refuse to compromise; you might resolve to fight to the end for your rights and actually do so in your advertisements, speeches and press releases. Given the better elements in the American people, it is possible for you by this means to win substantial support and defeat such a measure. The alternative course, and the one that business has unfortunately taken throughout the decades, is to compromise — for example, by making a deal conceding that the government can take over in New Jersey, but not in New York. This amounts to saying: “Washington, D.C., has no right to all our property, only some of it.” As with the burglar, the government will soon take over everything. You have lost all you have as soon as you say the fatal words, “I compromise.”

I do not advise you to break any law, but I do advise you to fight an intellectual battle against big government, as many medical doctors did, with real success, against Clinton’s health plan. You may be surprised at how much a good philosophical fight will accomplish for your public image, and also for your pocketbook. For instance, an open public fight for a flat tax, for the end of the capital gains and estate taxes, and for the privatizing of welfare and the gradual phasing out of all government entitlements is urgent. More important than standing for these policies, however, is doing so righteously, not guiltily and timidly. If you understand the philosophic issues involved, you will have a chance to speak up in such a way that you can be heard.

This kind of fight is not easy, but it can be fought and won. Years ago, a well-known political writer, Isabel Paterson, was talking to a businessman outraged by some government action. She urged him to speak up for his principles. “I agree with you totally,” he said, “but I’m not in a position right now to do it.”

“The only position required,” she replied, “is vertical.”

Citations & Notes

- 1 Ayn Rand, For the New Intellectual (New York: New American Library, 1961), p. 27.