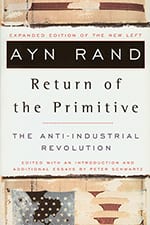

This article was originally published in the May 17, 1970, edition of The New York Times Magazine as part of a symposium on the question: “Are We in the Middle of the ‘Second American Revolution’?” It was later anthologized in The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution (1971) and Return of the Primitive: The Anti-Industrial Revolution (1999).

The New Left does not portend a revolution, as its press agents claim, but a Putsch. A revolution is the climax of a long philosophical development and expresses a nation’s profound discontent; a Putsch is a minority’s seizure of power. The goal of a revolution is to overthrow tyranny; the goal of a Putsch is to establish it.

Tyranny is any political system (whether absolute monarchy or fascism or communism) that does not recognize individual rights (which necessarily include property rights). The overthrow of a political system by force is justified only when it is directed against tyranny: it is an act of self-defense against those who rule by force. For example, the American Revolution. The resort to force, not in defense, but in violation, of individual rights, can have no moral justification; it is not a revolution, but gang warfare.

No revolution was ever spearheaded by wriggling, chanting drug addicts who are boastfully anti-rational, who have no program to offer, yet propose to take over a nation of 200 million, and who spend their time manufacturing grievances, since they cannot tap any authentic source of popular discontent.

Physically, America is not in a desperate state, but intellectually and culturally she is. The New Left is the product of cultural disintegration; it is bred not in the slums, but in the universities; it is not the vanguard of the future, but the terminal stage of the past.

Intellectually, the activists of the New Left are the most docile conformists. They have accepted as dogma all the philosophical beliefs of their elders for generations: the notions that faith and feeling are superior to reason, that material concerns are evil, that love is the solution to all problems, that the merging of one’s self with a tribe or a community is the noblest way to live. There is not a single basic principle of today’s Establishment which they do not share. Far from being rebels, they embody the philosophic trend of the past 200 years (or longer): the mysticism-altruism-collectivism axis, which has dominated Western philosophy from Kant to Hegel to James and on down.

But this philosophic tradition is bankrupt. It crumbled in the aftermath of World War II. Disillusioned in their collectivist ideals, America’s intellectuals gave up the intellect. Their legacy is our present political system, which is not capitalism, but a mixed economy, a precarious mixture of freedom and controls. Injustice, insecurity, confusion, the pressure-group warfare of all against all, the amorality and futility of random, pragmatist, range-of-the-moment policies are the joint products of a mixed economy and of a philosophical vacuum.

There is a profound discontent, but the New Left is not its voice; there is a sense of bitterness, bewilderment and frustrated indignation, a profound anxiety about the intellectual-moral state of this country, a desperate need of philosophical guidance, which the church-and-tradition-bound conservatives were never able to provide and the liberals have given up.

Without opposition, the hoodlums of the New Left are crawling from under the intellectual wreckage. Theirs is the Anti-Industrial Revolution, the revolt of the primordial brute — no, not against capitalism, but against capitalism’s roots — against reason, progress, technology, achievement, reality.

What are the activists after? Nothing. They are not pulled by a goal, but pushed by the panic of mindless terror. Hostility, hatred, destruction for the sake of destruction are their momentary forms of escape. They are a desperate herd looking for a Führer.

They are not seeking any specific political system, since they cannot look beyond the “now.” But the sundry little Führers who manipulate them as cannon-fodder do have a mongrel system in mind: a statist dictatorship with communist slogans and fascist policies. It is their last, frantic attempt to cash in on the intellectual vacuum.

Do they have a chance to succeed? No. But they might plunge the country into a blind, hopeless civil war, with nothing but some other product of anti-rationality, such as George C. Wallace, to oppose them.

Can this be averted? Yes. The most destructive influence on the nation’s morale is not the young thugs, but the cynicism of respectable publications that hail them as “idealists.” Irrationality is not idealistic; drug addiction is not idealistic; the bombing of public places is not idealistic.

What this country needs is a philosophical revolution — a rebellion against the Kantian tradition — in the name of the first of our Founding Fathers: Aristotle. This means a reassertion of the supremacy of reason, with its consequences: individualism, freedom, progress, civilization. What political system would it lead to? An untried one: full, laissez-faire capitalism. But this will take more than a beard and a guitar.