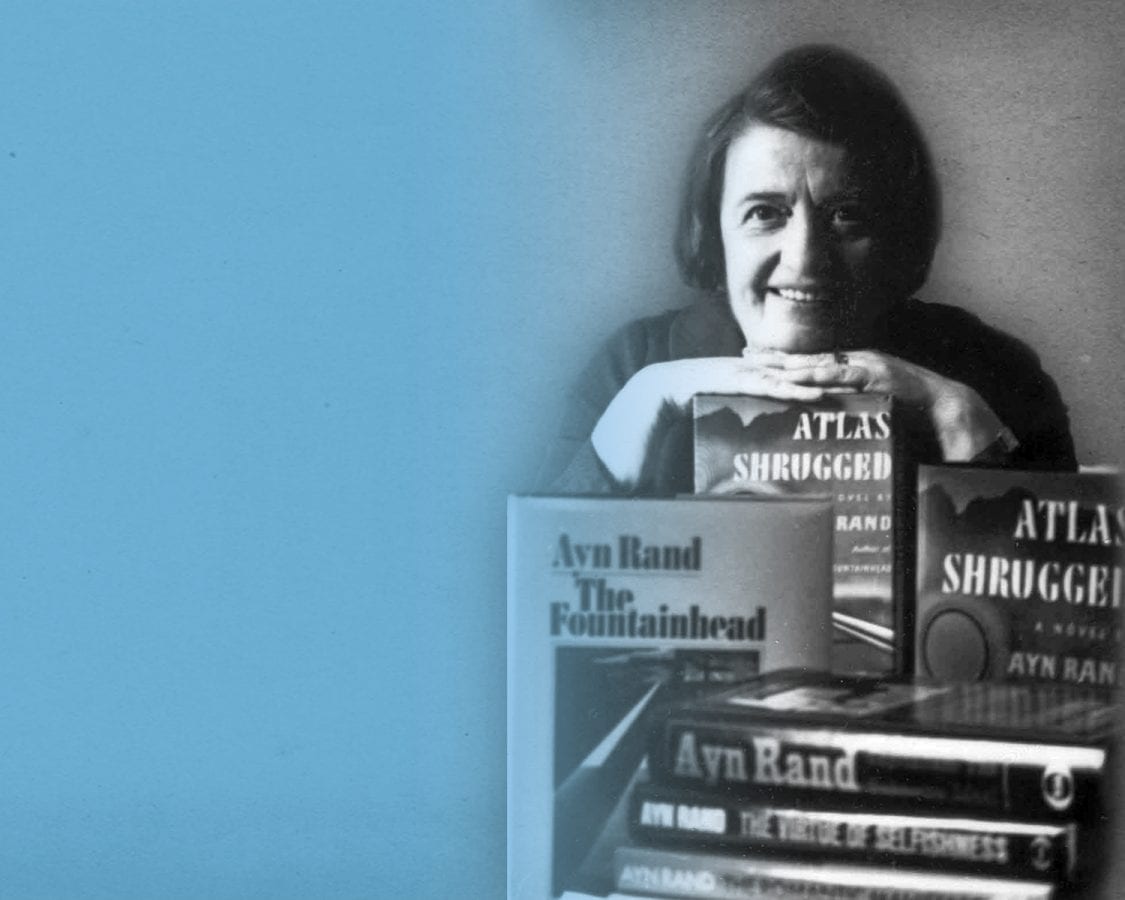

Ayn Rand Letters: Hollywood (1944 – 1949)

This is the first of four installments featuring previously unpublished Ayn Rand letters selected by Michael S. Berliner, editor of Letters of Ayn Rand. A total of forty letters have been divided into four groups for publication, according to general subject matter: Hollywood, fiction, nonfiction (including political activism), and more personal correspondence.

“While recently writing the complete finding aid to the Ayn Rand Papers, I noted some interesting letters that I hadn’t selected for the Letters book,” Berliner says. “Now, more than twenty years later, these letters struck me as meriting a wider audience. These unpublished letters were selected because of their insight into some particular topic or some aspect of Ayn Rand’s life, or, more often, as further evidence of how her mind worked on a variety of matters.

“I’d always been impressed by the care she took with non-philosophical issues and relatively trivial matters, and this mind-set comes across in virtually all of her correspondence. For a variety of reasons, she was not a ‘casual’ letter writer but always took great care to write with great precision on matters that today are usually relegated to a quick, unpunctuated tweet. For an explanation of her non-casual approach, see my preface to Letters of Ayn Rand on page xvi.”

The first group contains eight letters addressed to the following individuals on the dates listed:

- Bill Cole (February 20, 1944)

- Pincus Berner (September 24, 1944)

- Armitage Watkins (May 28, 1946)

- John Gall (November 15, 1946)

- Phil Berg (March 13, 1948)

- Alan Collins (September 18, 1948)

- Mario Profili (September 12, 1948)

- Gerald Loeb (January 8, 1949)

What follows is an introduction by Berliner to this installment, followed by the text of each letter with remarks from Berliner (always in italics) supplying necessary context.1

Please note:

- The letters published in this series are letters and not formal statements of Ayn Rand’s philosophic positions written for publication. Consequently, they should not be taken as definitive, and the reader should not exaggerate the importance of (a) possible ambiguities caused by her using informal rather than more precise language or (b) seeming conflicts with her published views. In all cases, her published statements are definitive.

- Photos, images, captions and footnotes are not part of Ayn Rand’s letters unless otherwise noted.

- These letters, owned by Leonard Peikoff, are part of Ayn Rand Papers collection. Their reproduction here is courtesy of the Ayn Rand Archives. The Ayn Rand Institute extends its warm appreciation to Leonard Peikoff and the Ayn Rand Archives, and also to Clarisa M. Randazzo, the volunteer who carefully transcribed all of the newly published Ayn Rand letters from the originals.

Ayn Rand lived in the Los Angeles area for two eight-year periods (the first from 1926 to 1934, the second from 1943 to 1951) so that she could work in the film industry. In the fall of 1926, she arrived in Hollywood with the hopes of starting a career as a film writer (having recently studied at the State Technicum for Screen Arts in her native Leningrad). After meeting Cecil B. DeMille on her second day in Hollywood, she became a film extra and then a junior writer for DeMille. When his studio closed, she worked at RKO in the wardrobe department, quitting when she sold a story to Universal. Then, with her first novel, We the Living, partially completed, she moved to New York City for the opening of her play, Night of January 16th, which subsequently had a long run on Broadway. She returned to Hollywood in late 1943 when The Fountainhead was sold to Warner Bros. with her as the screenwriter.

To Bill Cole (February 20, 1944)

Bill Cole worked as a reader for Paramount Pictures in New York under Frances Kane (later married to Henry Hazlitt) and Richard Mealand (who was instrumental in getting Rand’s manuscript of The Fountainhead to Bobbs-Merrill, which eventually published it). Rand likely met Cole at Paramount, where she and Cole worked under the same people just before her move back to Hollywood. Cole was also a friend of Rand’s brother-in-law Nick Carter and shared Carter’s sense of humor, writing to Rand that he (Cole) was out of favor at Paramount for demanding a “slight increase of $10,000 per synopsis, a 10-minute working day and a closed shop — closed to everyone but me.”

Dear Bill:

Please forgive me for my delay in answering you. You have no idea how terrible I am on the letter situation — because I come home from the studio utterly exhausted and fall asleep and can do nothing else. I only have weekends to answer mail — and I gave you a priority over letters I owe for several months. I hope this is not too late and that you will excuse me.

First of all — on the question you asked me about employment conditions here. I don’t know very much about the studios yet, except in the writing department, but as far as I can gather, the situation is this: the studios need help desperately only in the technical departments, such as cameramen, sound men, etc. If you know that angle and have had some such technical experience, you would probably have no trouble in getting a job. But in other, non-technical departments, they seem to be about normal and there are no unusual openings, as far as I have been able to learn. You write you’d be interested “in anything else even remotely connected with writing or editorial work.” There are only the two departments in such line — reading and writing. You don’t want the first, I understand they pay even worse than in New York. As to the second — it still seems to be the rule that studios do not like to give a writing break to an employee of their own from another department. I have heard stories of readers who had to leave their own studios and make a big success as writers on another lot. So I don’t think that getting a studio job in another line would get you closer to their scenario department. Except that nothing one can say about Hollywood is ever an iron-clad rule. There are always exceptions. Anything is possible here. It is very possible that you could come here, get some other job and have it lead you to writing. It could work that way. I can only say that, as a general rule, it doesn’t seem to. But it’s up to you — if you want to take the chance. Only it looks like a long chance.

From everything I hear here and from the record of every writer whom I asked how he got into screen writing — the shortest way seems to be outside the studios. That is, most of them came after establishing some sort of reputation in another line — playwrights, novelists and radio writers. They got in in one of two ways: either they had a reputation in some particular specialty, such as sports stories and the studio needed a sports story and hired this particular writer; or they sold something they had written and the studio got them with the property. If you want to try directly for the screen, my advice would be to write originals. They do buy originals from outside authors, not necessarily just from their own staff, and if they like an original enough, they will also hire the author to work on it for them. They don’t do it very often, but it does happen and there are writers who broke in that way. If you try in that way, I can tell you that what they look for in originals is the idea. It must have some new, startling idea in plot or theme — I don’t mean that it must be profoundly original in a literary sense, but new and different within the usual terms of screen stories. As, for instance, Norman Krasna here made a big hit with an original called “Princess O’Rourke.” (He was, of course, an established writer before that — but I am quoting it only as an example of what they go for in originals.) It was the story of a refugee princess marrying an American pilot. Nothing very new — but a good old trite situation given a modern angle they hadn’t used before. I don’t know whether you can write to order, that is, trying to aim at what seems to be wanted. I know I can’t. But if you can, this is the general line that seems to work here. Or — write an original any way that seems good to you, whether it’s the Hollywood way or not, and submit it. That’s what I would do. There is always the chance that it would hit the right person in the right way. And one chance is all you need. But to break in just as a junior writer, without selling them something, seems to be the most difficult of all attempts. It does happen — but it’s the longest shot. I’m afraid they’ll go on promising you a break and postponing it. I know a brilliant young writer here who has been in that position for over a year.

Your plan to go to Oregon and work on a farm seems almost too heroic. If you’re sure that you can stand the work physically and that you’ll have a lot of time for writing, it might be a good idea. If you do have a serious work you want to do — it’s an excellent idea. I wouldn’t be stopped by the mere fact of it being a dull existence — so much the better, you’ll write more. But I wonder about your doing farm work. That might be so hard physically, since you’re not used to it, that you won’t be able to write. I wonder why you picked out a farm. As far as getting a job, any kind, just to make a living and be free to write — there are a lot of openings here in Hollywood. Not in the studios, but every other place seems to be advertising “help wanted.” If you don’t care what work you do, you could probably find something better than farm work here. And then devote most of your time to writing. That is the best plan, I think. If you come here, I’d like to see you. Looks like I’m stuck here for a while — and I do miss the people I knew in New York.

Since this is such a long business letter, I won’t add much about myself, except to say that everything is going very well for me here. I am writing my own screen play — and the studio is very pleased with it so far. I have just signed a contract to stay here longer — until I finish the script. I am about half-way through it now. I love the work — and I do love Warner Brothers, since they’re so nice to me — but I hate Southern California. It is dull and flat, the climate and the very atmosphere — I don’t know about the people, haven’t had time to be very sociable. I hate the place for the very reasons most people like it — the sunshine, the palm trees, the going around in slacks, and all that.2 I love New York, always did and always will. However, if one doesn’t stay here permanently, it’s not too bad a place. I don’t mind it for a while. I’d hate to stay here forever.

Write and let me know if all this advice is of any use. And, of course, come and see me if you do descend upon California. I will be offended if you don’t. Incidentally, never mind your friends in Philadelphia, have you read my book? I think by now you should. However, I’m glad your friends liked it — give them my thanks.

Best regards and good luck to you from both of us,

To Pincus Berner (September 24, 1944)

Pincus Berner (1899–1961), a New Yorker, was Ayn Rand’s attorney, beginning with arbitration in 1935 against producer Al Woods regarding Night of January 16th.3 She became friends with “Pinkie” and his wife, who once took Rand to a lecture by British socialist Harold Laski, setting Laski in Rand’s mind as the main model for the character of Ellsworth Toohey in The Fountainhead.

Dear Pinkie:

Will you forgive the long silence from a dizzy and overworked writer? So many things have been happening to me so fast that I simply cannot catch up with myself.

To give you the briefest account of my events to-date: I finished the screenplay of “The Fountainhead” at Warners with great success. Henry Blanke, my producer, was very pleased and most complimentary about my script. It will go into production some time early in 1945, as a big special. No cast decided on as yet. Two weeks after I finished at Warners I had to start working on a new job — with Hal Wallis. You may have heard that he was a big producer at Warners and has just left them to form an independent company of his own. I have signed a five-year contract with Hal Wallis (with options, of course.) It is a very unusual contract, the kind that’s very hard to get in Hollywood — but I would not sign any other; this contract gives me six months off each year to work on my own writing; so that I give half a year to movie work and half a year to my own. I have just finished my first assignment for Wallis — an adaptation of a novel — and I rushed on it like all hell, since it’s to be his first production.4 I did a good job — because Wallis and everybody concerned are enthusiastic about it. So, believe it or not, I’m successful in Hollywood. Personally, I can’t quite believe it yet. But miracles will happen.

In the only two weeks I had off since I’m here, I went and bought a house. Or rather, an estate, 13½ acres, in Chatsworth, twenty miles from Hollywood. The house is ultra-modern, by Richard Neutra, all glass, steel and concrete. The house is a small palace, too wonderful to describe. We have ten acres of alfalfa, an orchard, chickens, rabbits, two ponds that go around the house, and a tennis court.5 Can you see me as a capitalist? And here I thought I was the poorest (financially) defender capitalism ever had. Frank has become a rancher, spends all his time working on the grounds and loves it. It was he who picked out the house — and everybody marvels at his good business judgment. We had to settle down here, since I will have to stay in California — and apartments here are simply impossible, in both cost and comfort.

This is a brief synopsis of my situation. Now to business matters. I have to become a California resident now and file my income taxes from here. I have not yet made an amended return since the first one you made early this year. I’ve [been] paying the installments according to that — but I suppose now is the time to change it, including my new income since then. I will have to have it done here, to establish California residence, and also because it is too complicated now to do it by mail. Would you send to me your original estimate of my tax for 1944, with all the details, deductions and reasons on how you arrived at the $1,000 I was to pay? I will turn it over to the tax-man of Berg-Allenberg, my agents, who does all the returns for their clients — and he will know how to amend it according to what I have earned since then.

I was told I will have to make out a new will, here, as a resident of California. How will that affect the old one I made, which is in your safe? The new one will be the same in content. Does it simply supersede the first one, or what is the correct legal procedure? Or should I keep both — to be filed in either state if anything should happen to me? All I want to put in the will is still that I´m leaving everything to Frank.

Bobbs-Merrill have sent me the full amount of my royalties for the first six months of this year, which is over $5,000. Apparently they forgot our agreement that they were to pay me only $1,000 this year and the rest on my next statement. Shall I keep the check — or return it and keep only $1,000? I think it will be all right to keep it, because I am told that my work at Warners on the screenplay cannot be considered as income from “The Fountainhead” by any standards. It is new work on salary — not income from a finished property. Besides, while I was at Warners, I worked on three other movies, besides my own, doing editing and rewrites for them. So my time at Warners cannot be charged to any one job. However, I don’t want to accept the Bobbs-Merrill check without your okay.

You asked me in your last letter how I could hate California when I’m successful here. I can still hate it geographically, as a place, and I do. I love New York, always will, and miss it terribly. I will probably go there for a visit, on my own time, just for purposes of morale. I feel like an exile here. A lot of people have been wonderful to me here, and I have actually become a celebrity here, but I miss New York people. And that means the Berners, too.

Best regards from both of us to you, Anne, Rose and Mr. Cane,6

To Armitage Watkins (May 28, 1946)

Rand received a May 24, 1946, letter from Armitage (“Mike”) Watkins of the Ann Watkins literary agency, which handled some of Rand’s works, informing Rand that he had “asked one of our authors (Donald Downes) in Italy to do a little research for us with respect to a rumored Italian-made motion picture of We the Living.” In Downes’s May 16, 1946, letter, which Watkins enclosed, Downes reported that Scalera Studios “made not one, but two movies [Noi Vivi and Addio Kira] from the book” and “both were extremely successful during the war years, not only in Italy but had a big box office in Germany and Vichy France.” The partial explanation, continued Downes, was that “both were made in cooperation with the Ministry of Popular Culture as semiofficial, fascist, anti-Russian and anti-leftist propaganda.” The Scalera brothers, he wrote, “were pretty deeply in the fascist stew and are not noted in Italy for their honesty. They are at present the darlings of the Hollywood crowd here and have paid highly to be darlings. They have most important friends at Allied Commission7 and are said to be fairly expert at buying other people’s lawyers.” Downes went on to recommend that, in any attempt to recoup funds, Watkins and Rand hire “a man so far removed by politics and history from the Scalera crowd that they would not even try to buy him . . . . I repeat I think it highly dangerous to take a lawyer because, before the war, he was the respectable correspondent of your New York attorneys.”

Dear Mr. Watkins:

Your letter of May 24th was certainly a bombshell to me. I am extremely indignant at the piracy of WE THE LIVING by the Italian producers, and at the use which they made of it. Thank you for finding this out for me. I shall now blast them with the kind of lawsuit which they deserve. I am amazed at the whole procedure, and can not understand how a picture company which is still in business could have done such a thing. How did they hope to get away with it?8

Movie poster for Noi Vivi (We the Living) Italian pirated version

I am writing to a very prominent attorney in Washington, who is a friend of mine and whom I would like to have handle the case for me, if he will undertake it. I think this will require the services of an international lawyer who has Washington connections.

I did not quite understand the sentence in Mr. Downes’ letter which reads: “I think it highly dangerous to take a lawyer because, before the war, he was the respectable correspondent of your New York attorneys.” Is this a warning specifically against the correspondent of Ernst, Cane & Berner, or against any representative of American law firms?

Have you any information on whether the Italian publishers of WE THE LIVING, Baldini and Castoldi, were involved in this matter in any way? Is it possible that they cooperated in the piracy or received any financial return from it? Were they in a position to stop the production of the motion picture and yet allowed it to be produced?

Fosco Giachetti and Alida Valli in Noi Vivi (We the Living) Italian pirated version

I have just received from Miss Nancy Brettner copies of the contract with Baldini and Castoldi for the Italian rights to THE FOUNTAINHEAD. I will have to wait before I sign this contract, to learn what their part was, if any, in the piracy of WE THE LIVING. If they had anything to do with it, I certainly will not sell them another book of mine.9

Do you know whether there are other such cases of American books being stolen during the war? The reference in Mr. Downes’ letter to the piracy of THE LITTLE FOXES would indicate that this sort of thing must have gone on in Europe on a grand scale. Can you find out for me what the other American authors are doing about it?

Please let me know what you think about this case, and I would appreciate any suggestions you and your mother can give me.

To John Gall (November 15, 1946)

Rand met John Gall (1901–57) in 1941, when Gall was the attorney for the National Association of Manufacturers. In her biographical interviews, she described him as “a violent conservative” (“violent” being her word for “extremely passionate”). She hired him in 1946 to handle her piracy claim regarding the 1942 Italian films of We the Living, and later he handled her lengthy and successful effort to bring Marie Strachov, her old Russian family friend and teacher, to America from a war refugee internment camp in Austria.10 This letter is indicative of the care Rand took with the details of non-intellectual issues affecting her career.

Dear John:

Thank you for your letter of October 31. Excuse me if I have taken so long to answer, but I am stopped by the necessity to make a choice of the Italian attorneys whose letters you sent me.

I have read these three letters very carefully and I don’t think I can really judge them clearly enough to make a decision. Do you want me to be the one to decide? Since I don’t know Italian legal procedure, I have no way of estimating these attorneys’ attitude or knowledge.

I think you can judge their competence from the letters much better than I can. Also, perhaps you may have reliable sources to check up on them in greater detail. I can tell you my impressions of the letters, but I would like you to take the responsibility of selecting the attorney you prefer yourself. I would only urge you not to make a decision until you are certain, and not to take anyone if you have any doubts or reservations against him. Please check as thoroughly as possible, or have someone, whom you can trust, check on them in Europe before you make a decision.

Now as to my impression of these three letters, I have noted a few doubts against all three.

- Mr. Luciani. He seems to suggest that he wants to be your permanent representative in Italy, as part of his condition for taking our case. I wonder if this is proper on his part. Also, I wonder whether what he calls “a mandate” or “warrant for law suit” (a copy of which you enclosed) is the proper thing for us to sign? This warrant ends on sentence: “He hereby promises to hold their action as firm and binding.” This seems to be a complete power of attorney which would give Mr. Luciani the right to dispose of the case in any manner he wishes. If I understood this correctly, I would certainly object to that. I think our Italian attorney should represent us, but the final decision on any settlement should be ours.

- Mr. Marghieri. His letter seems to show the greatest interest in the case. But, as you noted, I wonder how he found out that the case involves my book. Unless mine is the only book by an American author that has been pirated by an Italian movie company, this might mean that he has some connection with Scalera. Also, I do not quite like the fact that the Colonel Walton whom he gives as reference is not in Washington, but in Italy, which makes a personal check-up impossible.

- Mr. Graziadei. The fact that he is the attorney for a long list of American picture companies is both in his favor and against him. What disturbs me is the fact that in his first letter to the Ann Watkins office, Mr. Downes warned us that the Scalera Company has connections with the Hollywood crowd in Italy. Also, Scalera are making all kinds of deals with American picture companies here. So there is a possibility that the interests of one of the companies which Mr. Graziadei represents might clash with ours. If so, he would be in a difficult position, and I would rather not have an attorney with divided allegiance. Also, there is one point in Mr. Graziadei’s letter to which I object very much. He writes that: “No legal action is possible against the Italian film company if same has been authorized by Italian ministry.” Is he legally correct about that? Are we supposed to recognize as legal and binding the decrees of the Fascist government? If this point is open to doubt and interpretation, or is to be settled by the final peace treaty with Italy, yet Mr. Graziadei has already taken the above attitude in favor of Scalera — then he is certainly not the man for us, and I would reject him at once for this reason.

The above are my opinions of the three letters. I will be very interested to know whether my amateur legal judgement is correct. Let me know your own opinion of this — and please let me know the reasons of your decision before you commit yourself to the attorney you choose.

I am sending a letter to the Superfilm Distributing Corporation, in the form you suggested, and I shall let you know as soon as I receive an answer.

The Ann Watkins office has written to me that Baldini & Castoldi are very anxious to have me sign the contract for the Italian publication rights to THE FOUNTAINHEAD. May I sign it or are you still uncertain as to how it will affect our case under Italian law? If it is too early for you to tell, I will not sign it now — there is no reason for me to hurry on this. But if you think that this will not affect WE THE LIVING at all, then let me know.

With best regards.

In his November 27, 1946, response, Gall wrote: “Your very discerning comments will be helpful in ultimately settling upon a suitable Italian attorney.” Gall ultimately recommended Marghieri, and, in 1961, Rand received a settlement of approximately $23,000 from the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission.

To Phil Berg (March 13, 1948)

Phil Berg (1902–83) and Bert Allenberg were Rand’s agents “for the motion picture industry,” beginning in 1944 and ending in 1948. In a 1983 obituary for Berg, the New York Times described him as “a pioneer talent agent” who “was considered the originator of the package deal — a concept which changed the basic structure of Hollywood. . . . Berg-Allenberg represented the cream of Hollywood’s movie stars, directors and writers.” In her biographical interviews, Rand commented: “They were my agents only through Alan Collins, because they handled all his clients, and I disliked them enormously. They were top agents, but I don’t know any agents in Hollywood that would be honorable.”

Dear Phil:

Thank you for your letter of March 10 and for the copy of the wire which you sent to Alan Collins.

Mr. Blanke’s attitude, as suggested in your wire, is a very grave matter, of which I was not informed. Since my “argumentative proclivities” is a statement that has extremely serious implications, would you please let me know the full particulars about it? Please tell me exactly what Mr. Blanke said, on what date, and to whom? Was it to you personally?

What “interminable discussions with Ayn Rand” do you refer to in your wire? The last time I saw you was on June 9, 1947, at your offices. The last time I saw Bert Allenberg was on September 23, 1947, in the Hal Wallis office.

In regard to the present matter of THE FOUNTAINHEAD, I have had one discussion with Jimmy Townsend of your staff, in Mr. Coryell’s office, on February 19, which lasted about half-an-hour. Thereafter, I had three telephone conversations with Mr. Townsend. The gist of these discussions was as follows:

In the office, on February 19, I told Mr. Townsend the understanding which I had with Mr. Blanke, as Mr. Blanke had said it to me repeatedly, on numerous occasions since 1944: that he (Blanke) considered that my script of THE FOUNTAINHEAD needed only about one week’s editorial work which he wanted me to do when he had a director and cast assigned to the picture, that he would have no other writer on it, and that the picture would be made in accordance with the spirit and intention of my novel. Mr. Blanke and I had never had a disagreement. I asked Mr. Townsend to inquire about Mr. Blanke’s present plans and particularly whether Mr. Vidor had some writer of his own which he might want to bring into the picture. On this last, Mr. Townsend assured me emphatically that Mr. Vidor had not.

On the next day, I called Mr. Townsend to ask him a question which, in our rushed conversation of the previous day, I had neglected to ask, and which was: why had your office not informed me about the fact that THE FOUNTAINHEAD was going into production, when you had knowledge of it well in advance, yet I was left to learn it from the newspapers? Mr. Townsend said that I was right in feeling that your office should have informed me, but that this was no more than regrettable oversight.

Shortly afterwards (I believe it was the next day, but I did not mark the date on my calendar), Mr. Townsend called me to report on the situation. He told me that he had spoken to Mr. Blanke and that Mr. Blanke had confirmed to him our understanding just exactly as I described it, including the fact that the script needed only one week’s work which I was to do. Mr. Townsend said that the production of the picture was not definitely set, owing to budget difficulties, that Mr. Blanke and Mr. Vidor were now working on the budget and that they could undertake nothing definite until the return of Mr. Jack Warner, which was expected within a week. Then, if they found that they could make the picture now, I would be called. Mr. Townsend also stressed the fact that Mr. Vidor had told him personally that he wanted to discuss the picture with me.

On March 3 or 4, having heard nothing from Mr. Townsend, I telephoned him to ask whether Mr. Warner had returned and what had been decided. Mr. Townsend said that Mr. Warner was back, but no decision had been made, and that the “production office” was still working on the budget. Then Mr. Townsend added that Mr. Vidor had a junior writer working with him on the script, but — these are Mr. Townsend’s words as exactly as I remember them — “I have checked and they assured me that no writing was being done on the script.” When I asked what the writer was doing in such case, Mr. Townsend said: “I don’t know. It’s just somebody for Vidor to talk to, I guess,” Since there were too many contradictions here, I said that it was imperative that I see Blanke or Vidor or both. I stressed that it did not have to be a business appointment about a job for me, but a social appointment so that I would be acquainted with the situation. I said that particularly in the case of Mr. Vidor, your office should have arranged such a meeting long ago, without any request from me — which is the usual practice in Hollywood. Mr. Townsend said that he couldn’t arrange it, because “they weren’t ready to say anything.”

This is the last I heard from your office, until the receipt of your letter of March 10.

Which information in the above discussions do you refer to when you say in your wire to Alan Collins that “Blanke who knows Ayn’s argumentative proclivities refused [to] meet with her. She was tactfully informed.”?

Don’t you think that the matter is much too serious for “tact” and that I am entitled to a full and exact report on the situation?

I will appreciate your personal attention and reply,

Rand’s papers contain no response to this letter. The last letter from Phil Berg, dated September 24, 1962, is a friendly, newsy update of his activities (including his being a subscriber to Rand’s Objectivist Newsletter).

To Alan Collins (September 18, 1948)

Alan Collins (1904–68) was Rand’s literary agent at Curtis Brown Ltd. from 1943 until his death in 1968. That agency still handles her books. The following seventeen-page letter (marked “Confidential” in her handwriting on the first page) was not included in Letters of Ayn Rand because, although it was sent in the mail, it is more of a report than a piece of correspondence. It is, by that token, a unique written account by Rand of detailed events in her life and an indication of the kind of detailed narrative that must have comprised the lengthy letters that she sent to her family in the Soviet Union, letters that were destroyed during the siege of Leningrad and of which she had made no copies.

Dear Alan:

As I promised you in our telephone conversation yesterday, here is a complete account of my dealings with Berg-Allenberg during the writing and production of THE FOUNTAINHEAD at Warner Bros.:

As I wrote to you at the time, I do not believe that it was the efforts of Berg-Allenberg that got me the job at Warners to write the screenplay. I was called by the studio shortly after you had entered the situation and after Mr. Swanson was ready to take me over as a client.11 Also, I had discussed the situation with Mr. Herbert Freston, who is my attorney here and who is also attorney for and Vice-President of Warner Bros. He promised me at that time to look into the situation. It was shortly after this that I was called to go to work. I suppose that I shall never know the exact truth of what happened, but it is my conclusion that I owed this call to Mr. Freston and yourself — not to Berg-Allenberg.

Things went extremely well at the studio from the day I started to work there. I had no trouble or disagreement of any kind with Mr. Blanke, the producer, and King Vidor, the director. During our first interview, on March 23rd, Blanke and Vidor told me that it was their intention to make a faithful adaptation of THE FOUNTAINHEAD, to preserve its theme intact and to produce, in screen terms, an equivalent of the book in literary terms. Blanke said: “I want the people leaving the theater to have the impression that they had seen the whole book, and to get from the picture the same feeling they get from the book.” I said that if that was their intention, we would be in complete agreement from then on — and we were.

When the first fifty pages of my script were mimeographed, the front office was extremely enthusiastic about it. Jack Warner stopped me on the lot several times to tell me so in person. Jimmy Townsend, of the Berg-Allenberg office, told me that Warners had informed him how pleased they were with my work, and he added that it was quite unusual for a studio to express enthusiasm in the middle of an assignment. Then I told him that if things went on as well as this, I would like him to take up with Warners the possibility of their buying my contract from Hal Wallis. I had two reasons for this idea: (1) I was much happier working with Blanke than I had been with Wallis and felt that his taste in pictures was closer to mine. (2) Since Wallis cannot sell my contract without my consent, I thought that if such a deal could be arranged, I would make it a condition that I would take off all the time I needed to finish my novel and would then give to Warners the time I still owe to Wallis on my contract. Jimmy Townsend said that he had had precisely the same idea, and that it would probably be difficult, because Wallis would not agree to sell my contract, but that he, Townsend, would take the matter up with Warners when I finished the script of THE FOUNTAINHEAD.

Sometime during the writing of the script, King Vidor told me that it would be wonderful if I could stand by on the set during the entire shooting of the picture. I had never mentioned the subject, he brought it up himself. He said that we could work out a lot of very interesting things together and that the experience would be valuable for me, that I would learn a lot about picture making. I told him that I would be more than delighted to do it, with or without payment. This was not a business proposition or a commitment on Vidor’s part, it was just a discussion. I did not press him about it, but I reported the conversation to Jimmy Townsend and told him that I was more than anxious to be present during the shooting, so that if any changes were made at the last minute on the set, I would be there to make them. Townsend said it would be a cinch to arrange, particularly if Vidor wanted me on the set, and that he, Townsend, would arrange it as soon as the script was finished.

Things went on very smoothly, and I kept hearing nothing but compliments all over the lot. Everybody was pleased with the script and with the rapidity or our progress.

When we were approaching the completion of the script, I told Jimmy Townsend that the time had come to make an arrangement with the studio for me to remain on the set during the shooting of the picture. I made it clear to Berg-Allenberg that my sole and most crucial interest in the whole business was to protect the integrity of my script, to protect it from hasty or accidental changes, that I needed all the help which they, as my agents, could give me in this respect, and that it was the only thing I wanted. I explained how disastrous careless changes in script could be in a picture which has such a dangerous, controversial theme. Berg’s attitude, in effect, was: “Aw, they always make script changes in Hollywood, and your picture is no different from others.” I am not sure whether he has ever read my book or not.

Jimmy Townsend reported to me, after a while, that he had tried and been unable to arrange for my remaining on the set. He said the studio had a rule against permitting writers on the set. He was somewhat sad and evasive about it. This was one major request of mine, which Berg-Allenberg had promised me to accomplish — and had failed.

After that, I asked Vidor in person how he felt about this matter. He became strangely evasive. Up to that time, I had heard nothing but compliments from him, and he had acted as my enthusiastic friend. Now I began to suspect that he had wanted to get a script from me (he had said that I was the only one who could write that script) — and then get rid of me, in order to have a free hand and to defeat any possible influence I may have on Blanke. Blanke does respect my opinion, and his artistic taste is very similar to mine.

I made no further issue about remaining on the set and did not insist on it. It was not essential to me to be present during the shooting — my sole concern was to be on hand to protect the script from random changes.

By June 12th the script, which was called “Revised Temporary”, was finished, and on Monday, June 14th, we started on the Final script. The work consisted of Blanke, Vidor and me reading the script aloud and discussing every possible cut or change for the final editing. We were working very fast and thought that one week was all we would need to finish. But on Wednesday Mr. Blanke became sick and stayed home that day as well as Thursday and Friday. So we were held up on the editing.

On that Friday, June 18th, at about 12:30, Vidor telephoned me in my office and told me the following: Blanke had just called him from his home and told him that the studio had informed him, Blanke, that I was to be closed, that is, taken off salary, the next day, Saturday, the 19th, that this had come from the front office without any explanations and that Blanke was on his way to the studio, even though he was sick, and that he would be there at 2 o’clock.

I must say at this point that I still don’t know what was the reason for this incident. Blanke assures me that it was merely the usual policy of the studio, that they are always very anxious to take people off salary as soon as an assignment is finished and that they had probably figured that this week was all we needed for the final script. This may be true, but on the other hand, I have a strong suspicion that Vidor’s influence was behind this. I suspect that he was anxious to do the final editing himself.

The moment Vidor called me about this, that is, at 12:30, I telephoned Phil Berg. I told him what had happened and asked him to come to the studio at 2 o’clock, because something had to be done and I needed his help. We were only about halfway through the script — we had edited about 80 pages out of 150 pages, so we could not possibly finish it that afternoon and the next day. Berg got furious at me for asking him to come to the studio. He said he was booked solid for the whole afternoon, had a string of appointments with very important clients, and told me that I was not the only client he had. He said that his presence at the studio was not necessary, since I had not received an official notice that I would be closed off the next day. I repeated that Blanke had received the official notice and that Vidor had just told me so. Berg answered: “Vidor is not an official of the company. Never mind what he says.” (?!) I asked him what I was to do at the conference with Blanke at 2 o’clock. Berg said that I should do nothing, just ignore the whole thing, that he would come to the studio on Monday and straighten everything out, but he could not come that afternoon. You know, of course, that if I had been closed out officially on Saturday, it would have been impossible to get me back into the studio, because they would have considered the script finished and would have left Vidor or whoever to edit it without me.

At 2 o’clock Blanke arrived at the studio and confirmed what Vidor had told me, that is, that the front office wanted to close me next day, because the budget of the picture was very tight and they had expected the script to be finished that week. Blanke and Vidor both seemed to be panicky about this and did not know what to do. Blanke said that we should have my agent here to help him fight for me at the front office. I suggested that he call Mr. Berg himself. Blanke asked Vidor’s secretary (we were in Vidor’s office) to get Berg on the wire. She telephoned and gave us the following report, as nearly verbatim as I can remember it: “Mr. Berg is away on his yacht for the weekend. Mr. Allenberg and Mr. Townsend are away for the weekend. There is nobody at the office except Mr. Coryell.” (Coryell is the business manager at Berg-Allenberg and cannot do any studio negotiations.) We were completely stuck and did not know what to do next. Then I made the following proposal: Since we had about another week of work to finish the script, I said I would finish it without payment — in exchange for an agreement that all future changes in the script during the shooting would be done by me; and, for that purpose, I would remain in the studio, in my office, doing my own work, but would be available any time they needed me and would do the changes for them without salary. Blanke agreed to it. He and Vidor went to see Mr. Trilling, who is Jack Warner’s assistant, to obtain his approval. They came back and told me that Trilling did not know whether they could accept such an unconventional arrangement, but he had agreed to let me remain on salary for another week to finish the script.

On Monday morning Berg telephoned me to ask what had happened. I had barely begun to say: “We called you and were told that you were away on your yacht —” when he literally blew up and started screaming that he’ll be damned if he didn’t have the right to go away on a weekend and wasn’t he entitled to a rest? Mind you, I had not even reproached him yet. I told him that I was not arguing about his right to his weekend, but why had he found it necessary to tell me that he was booked solid with appointments? He kept screaming in self-defense, telling me how difficult I was, and ended up by saying that he would come to the studio.

I was in Vidor’s office when Berg arrived. We told him what had happened. Berg’s whole attitude was one of antagonism toward me. I asked him to make the final arrangements with the front office for me to remain in the studio during the shooting of the picture — though not necessarily on the set. I pointed out to him that if the picture was preserved intact as we had it now, I would give it all my support. If the picture was mangled, I would have to come out against it and tell the public that it was not a movie of THE FOUNTAINHEAD. I said that this was the possibility I wanted to avoid and it would be best for the studio’s interest and mine to protect us against it. At which point, in Vidor’s presence, Berg said: “Oh, if you came out against the picture, it might even be good for it.” (Alan, I will let you judge whether you think as I do, that this was perhaps the most dreadful thing an agent could do to his client.) Then Berg said he had to speak to Vidor, and he would speak to me later, and I went back to my office.

Sometime later Berg came to my office and again started the discussion in a tone of hysterical anger. I cannot understand why every business conversation I have had with Berg has always started with an angry attack on his part. He began by saying that people on the lot were complaining about how difficult I was. I had dealt with no one except Blanke and Vidor, and there had been no quarrels among us. I asked Berg to tell me in what way I had been difficult, to name the specific instances he meant and to name the persons who had complained. He refused to answer. Then, he launched into a long speech exactly as follows: My commission amounted to only a hundred dollars a week. He had to give half of it to you. The income tax of Berg-Allenberg took some huge percentage of their income (he told me the exact figure, but I don’t remember it), he went into minute financial details of their costs, etc., — and ended by saying that they got only something like 33 cents a week out of my commission — and they had clients who were directors making $12,000 a week! I think he caught himself in time, because suddenly and very hastily he added: “But of course, we will work for you just as hard as for anyone else, just the same.” I told him that I quite understood his point, that I did not want anyone to work for me as a favor, that I had never been a charity case in my struggling days and did not intend to be one now; and therefore the best thing to do was for Berg-Allenberg to let me go, as I had asked them before to let me go. At this point, Berg came back to his senses, I think, and became much more calm and almost friendly. He assured me that I had misunderstood him and that they would not let me go. Then he promised to make the arrangement with the studio for me to remain in my office — as I had proposed it to Blanke on Friday.

Later in the afternoon, I was in Vidor’s office, working on the script with Vidor and Blanke, when the door opened and Berg flew in. He seemed to be very cheerful, he said that he had made the arrangements with Mr. Trilling, that Mr. Trilling had okayed it and that after this week I would remain in my office without salary to stand by for possible script changes during the shooting. I said that was fine and would he please draw up the necessary documents in writing. He said something like “sure” and flew out of the office again.

I heard nothing more from him during that week. We finished the script on Friday, June 25th, except for a few minor things which I had to do at home on Saturday. I went home Friday night on the understanding that I would be back at the studio on Monday, but without salary. Blanke told me to write him a letter stating our agreement, and that it would probably be all that was necessary to cover it.

On Saturday I wrote the letter, a copy of which I am enclosing. On that same Saturday, Finley McDermid, the head of the scenario department, called me at home to tell me that the studio had changed their mind about our agreement, that they did not want me to work free nor to remain on the lot; that they would call me back for any script changes, if such came up, and that they would then pay me for the work by the day. I telephoned Phil Berg. He said that he was terribly sorry, but Jack Warner, who was just then leaving for Europe, had cancelled our agreement by reason of it being unprecedented. I said I understood that it was an unwritten law of the studios that one could not cancel a verbal agreement during the period when it was being committed to paper. (Do you remember how you had assured me of this at the time Warners bought the rights to my book?) I asked him [why] hadn’t he arranged to have the agreement in writing. Berg kept saying, “What can I do? There is nothing I can do. They just changed their minds.” This was the second incident where Berg-Allenberg promised to achieve a request of mine — and failed.

I saw Blanke the next week. He gave me his word of honor that there would be no changes made in the script during the shooting, except by me; that if any changes became necessary, he would call me to make them and I would be paid for my work. I said that I would not agree to work by the day and to be on call in this manner, unless it was on the condition that all changes in the script would be made by me. If Blanke were willing to guarantee this condition, I would work in any way he pleased, with or without payment, at the studio or at home, any arrangement he chose would be agreeable to me, so long as this one condition about my making all the changes was observed — the rest did not matter to me. I said that I would not sign any agreement about my future work, if this condition was not included. He said: “Let it go without any signatures and leave it to me. You will see that the script won’t be touched. I give you my word of honor.”

I told my whole story to Mr. Freston. He spoke to Trilling and told me that Trilling assured him he, Trilling, had never made the agreement with Berg, which Berg announced to us as made. However, Trilling assured Freston that I would be called back should any script changes become necessary.

I must mention that King Vidor too, gave me his word of honor that he would make no changes in the script without me. But, by then, it was my impression that Blanke wanted me to remain on the lot, and Vidor did not.

The picture went into production, and everything went smoothly. Blanke telephoned me quite often and very faithfully to consult me about small changes in the script. I did the changes for him right over the telephone. He told me that I could visit the set any time, but I did not want to do it too often, if Vidor was afraid of my presence, as I think he was. I came a few times to see the shooting and did some minor rewrites right on the set. None of this work involved a whole day, and, therefore, I was not paid for it and did not ask for any payment. I am told that the picture was shot verbatim, as I wrote it, with no adlibbing or improvising by anyone on the set. As far as I know, Blanke, Vidor and the studio did keep their word to me. Everything was fine and I felt very happy about it — until Wednesday, September 15.

As you probably know from the book, the most important and crucial part of the story is the speech which Roark makes at his trial. This was the most difficult thing to write in a condensed form, and the most dangerous, politically and philosophically, if written carelessly. We had many conferences about it. There were all kinds of objections and I rewrote the speech many times until all the objections were met.

Here is a list of the conferences we had about this speech — not counting the numerous conferences among Blanke, Vidor and me while I was writing the script:

June 14 (?) Mr. Shurlock of the Johnston office,12 Blanke, Vidor and I.

July 2 Judge Jackson, Mr. Shurlock and another gentleman from the Johnston office, Blanke, Vidor and I.

Aug. 31 Mr. Freston, Mr. Williams (his assistant), Gary Cooper, Mr. Prinzmetal (attorney of Gary Cooper), Blanke and I.

Sept. 1 Mr. Freston, Mr. Williams, Blanke and I.

Sept. 2 Gary Cooper, Blanke and I.

Sept. 2 Mr. Trilling, Blanke and I.

Sept. 8 Blanke, Vidor and I.

Sept. 8 Mr. Trilling, Blanke and I.

Except for the first one, all these conferences took place after I had finished the script. Blanke called me back to the studio for these conferences. I had to work for several days on rewriting, at different times, and the studio paid me for these days. I don’t have to tell you how excruciatingly difficult this work was. But I did not object to making changes — so long as I could preserve the theme of the story and the philosophical ideas of the speech. Altogether, from my first temporary script on, I rewrote that speech six times.

The last objection raised to the speech was from Vidor — on September 8. He found that the version which we made after the conferences with the attorneys was less dramatic than our previous versions — and he was right. So I rewrote the speech once more. And this final version was really the best one. Everybody okayed it and everybody was very pleased with it, including Vidor. He did not make a single suggestion or criticism, nor ask for any change in this last version. He said it was fine and just right. He told me this, and later said the same thing to Blanke.

You realize, of course, that this speech had to be written as carefully as a legal document. I had to weigh every word, every thought — in order not to leave any loopholes which would permit anyone to accuse us of some improper ideology. I had to make every idea crystal clear, cover every possible implication, guard against any chance of misunderstanding, avoid any possibility of confusion. I did it — and preserved the dramatic and literary qualities of the speech at the same time. You understand the problems of writing. Try to imagine what sort of effort this took.

Blanke and Vidor asked me to coach Gary Cooper in the reading of the speech for a voice recording. I did. The recording came out excellently. I asked both Blanke and Vidor whether they thought the speech was too long (it ran about six minutes) and told them that there were certain cuts which could be made. They both said, “No,” they did not want it cut and did not find it too long. Blanke said, “Every word of it holds. I want it just as it is.”

It was agreed long ago that the one scene which I would see shot would be the courtroom scene. This was the last scene of the picture. I came to the studio for the first two days, when all the preliminary shots were taken which precede Roark’s speech. Everything went along beautifully, and I can’t quite tell you what a wonderful mood prevailed on that whole set. Everybody was enthusiastic about the picture. It was just coming to an end triumphantly. I was extremely happy and thought that now, at last, I can relax and feel at peace, the picture was safe.

On the third day, which was Wednesday, September 15th, I came on the set a little after 10 o’clock (the set is called for 9, but the first hour is taken up with lighting and setting up the camera, and Blanke had told me to be there by 10.) Just as I came on the stage, the bell rang for the next take, and what I saw being done was this: Vidor was taking a shot of Cooper starting his speech from the middle, cutting out the entire first third of it.

The cut made the whole speech senseless and left glaring holes in the political theory of the speech, making it open to every kind of attack, objection or smear. The speech could be construed as anarchism or fascism or simply plain drivel; with the first third taken out, one could not tell what the character was talking about. Imagine a carefully devised, complex legal contract with the first two pages torn out of it — and visualize what sense or meaning would be left in the remnant.

I waited until they finished the shot and then asked Vidor what he was doing. (Incidentally, and on my word of honor, I did not raise my voice. I spoke very quietly because I did not want the people on the set to know that there was any trouble.) Vidor said that this was just a protection shot, that he had already shot the first part of the speech as written and that he was taking this in case the speech needed to be cut later. I asked him why he had not told me about this and he answered: “Because you were not here.”

I went to the telephone and called Blanke. He came on the set and told me that Vidor had called him at the last minute, at 9 o’clock that morning, and asked permission to take this “protection shot” which he, Vidor, had apparently devised then and there, on the spur of the moment; Vidor told him that the request came from both himself and Gary Cooper. Blanke told me that he had given Vidor permission to do it, even though he, Blanke, did not intend to use this cut; he had given in only to keep Vidor and Cooper contented and get a good performance out of them for the rest of the day. I told Blanke that this was a cut which we could not make, that if cuts were necessary, I could tell them where to make them, but this one simply blasted all sense out of the speech. Blanke agreed with me, we called Vidor aside. Vidor got very nasty; he had no reasons or explanations to offer except that he had felt (!) he wanted to make this “protection shot.” There was no time to argue on the set, so we left.

I went with Blanke to his office. He kept assuring me that this cut would never be used. I was literally shellshocked. I could not grasp (and still can’t) how they were able to make such a decision (even as an alternate possibility) so lightly and carelessly, after all those conferences, legal discussions and the brainwracking, careful thought we had all given to that speech. I could not understand how it was possible that they had consulted me about every little thing, every small doubt, during the shooting of the picture — and then had done this in the most crucial, most dangerous point, done it on the spur if the moment, knowing that this speech was more important to me (and to the film’s future prestige or disgrace) than all the rest of the picture. Both Blanke and Vidor had thus broken their word of honor to me.

I told Blanke that if this cut were considered, if it remained in existence, I would have to take my name off the screenplay and break off all connection with the picture. I could not sign my name to the speech in that form. I could not let my political reputation be smeared by the kind of attack which that speech would provoke and deserve. Blanke kept assuring me that the cut version would not be used and that he had permitted it to be shot only in order to appease Vidor. I felt certain that this was a deliberate double-cross on Vidor’s part — he had simply high-pressured Blanke to do things his way when there was no time to argue. I found out later from Gary Cooper himself that he, Cooper, had not raised any objection to the length of the speech and had not asked for any cuts that morning. (Incidentally, as just a minor touch of insanity, when Vidor read my last version of the speech, he said, “If there are any more changes, whatever you cut, don’t cut that first part” — because the first part of the speech was the one he seemed to like best.)

I asked Blanke for some form of written guarantee that this cut would not be used. I pointed out that their action had broken our agreement, and they had no legal right to all the work I had done after the completion of the script, because all that work was done on the express condition that I would make all the changes in the script, if and when they wanted changes made. They have no signature from me giving them the right to use that later, extra work. Blanke was actually very nice to me and very upset. He realized that he had been high-pressured and that he should not have given in. But he said that he could not give me a written guarantee about that shot, because it would upset all studio precedents.

He took me in to see Mr. Trilling. We had a long conversation. Trilling was very friendly and kept telling me, in effect, the same thing — they cannot give me anything in writing, but he gives me his word of honor that I would be consulted about the final form of the speech and about cuts in it, if cuts were made. I kept insisting I wanted a guarantee in writing and only in relation to this particular shot. They did not know what to do. They did not want me to leave, but they would not give me the thing in writing. I wanted to go home then, but Blanke asked me to wait and he went in to see Jack Warner. He came back and said that Warner sends me his love and tells me not to worry, that he gives me his word of honor that I will be in on the final film editing of the speech. Then I asked Blanke to let me see the rushes of the whole speech tomorrow, and said that I would hold my decision until then. We parted on this, with everybody in the studio expressing their regrets to me about the whole incident.

The next morning Phil Berg called me and started by bawling me out. He told me that Blanke, Trilling and Warner were furious at me and went on and in this manner, telling me the exact opposite of what I had seen the day before in the attitude of those to whom I had spoken. Berg accused me of coming on the set, screaming and ordering the shooting stopped. (?) He said that he had spent two hours at the studio yesterday “fighting for me” and that it was all settled: everybody had promised that I would be called in on the final editing and we didn’t have to discuss it any further. I asked him how it could be “all settled” without my consent, who had called him to the studio when I hadn’t, and if he was at the studio, why hadn’t he come to hear my side of it before he discussed anything? He said he had been told that I had already left — while I had been at the studio, in my office, until 6 o’clock. I told him that the matter was not settled, as far as I was concerned.

Blanke called me a little later to tell me about some retakes he had ordered Vidor to make (not in connection with the speech), and I asked him for an appointment to see him together with Phil Berg. I thought that I had better bring Berg’s part in this out into the open. Blanke gave me the appointment very nicely, almost eagerly, for 2 o’clock that afternoon. I called Berg and told him this. He refused to come. He said the he had other appointments and told me again that I was not his only client. He said that he would send Jimmy Townsend, if I wanted him. Then added that “Townsend is a very high-priced executive and I don´t see why we should waste his time on this.” I did not argue or insist. I said that I did not want Townsend to come and that I would go to the studio alone.

You realize, of course, that I had needed an agent very badly the day before, to fight for me, because my whole screen career hung in the balance. If I had had an agent whom I could trust, the first thing I would have done would have been to call him. But I knew that I could not count on Berg’s help, so I preferred to avoid another nasty fight with him and leave him out of the case entirely. Yet now, he had entered the case and, apparently, not for me, but against me. I had not once seen him do any negotiations on my behalf. Now I had offered him a chance to do it, to stand by me openly and in my presence. This would have been the best way to prove to me that my suspicions were unjustified. (I did not tell him this, but that was my purpose in asking him to come.) He refused to do it.

I went to the studio alone. I spent most of the afternoon talking to Blanke. I promised him finally that I would not break with the studio now, but would first discuss the matter with Mr. Herbert Freston who was then out of town. That afternoon, Jack Warner saw the rushes and called Blanke while I was in the office to tell him that he liked my version of the speech, both in content and photography, and that mine was the version he wanted to be used. I felt a great deal better. Then Blanke took me to see the rushes. My full version of the speech was so superior in every way, not only in content, but in the quality of the shot and in Gary Cooper’s acting, that there could be no question as to which of the two versions was better. Blanke promised me that I would see the whole rough cut of the picture by the end of this coming week. I told him that I will wait until then, that I would make no trouble and no demands if the picture remains true to my script and most particularly if they preserve Roark’s speech. This is how its stands at present. I have not heard from or called Berg since.

It is my impression that the studio will keep their word, because they actually do agree with me and also because they do think that my name on the picture and my endorsement of it are valuable and important to them. The studio publicity has been featuring me in all their publicity, and one of the men there told me the following: “We have nothing to sell in this picture except Gary Cooper and your book — and for our purposes, the name of your book is even more important at the box office than Gary Cooper’s, because your book is so famous.” If this is the studio’s attitude, I am certainly more than delighted to cooperate, and it is certainly to our mutual advantage, both for me and the studio. But you can imagine what kind of pressure will be brought upon the studio heads when a few people see the picture and begin to express opinions. All the opinions, of course, will be contradictory, because the story is so controversial. I think that Blanke and Jack Warner will carry it through in the proper way, that is, will leave the script untouched — but this is the time when I need the help of an agent to argue for my view point, if necessary, and to stress to the studio the value of my name and support, should the studio heads be tempted to weaken and give in to some pressure such as Vidor’s. (Vidor had seemed to be in complete agreement with us — but now, after this double cross, I do not know what his real opinion is and what to expect of him). I told Berg, in our last telephone conversation, that he should stress my value to the studio and I quoted the remark of the publicity man. Berg answered: “Aw, Ayn, you’re crazy. Who told you this? Probably some $40.00 a week publicity guy.” Dear Alan, please tell me whether this is an agent who is working for me, who is making proper use of my professional value and protecting my interests.

This is another matter where I needed Berg-Allenberg’s help — and they failed me. As to my request to Jimmy Townsend that he discuss with Warners the matter of their buying my contract from Hal Wallis, I have never heard a word about it. I don’t know whether Berg-Allenberg have bothered to do anything about it. I have not reminded them of it. I think they have simply forgotten. It is my impression that they don’t give a damn about my career.

Well, this is the whole story. I have spoken to Mr. Swanson on the telephone and he told me that he would be glad to take over any moment I say, and that he would sign with me any kind of contract that you decide on. He was very nice and quite frankly enthusiastic about getting me as client. That, of course, is what I want — I have no desire at all to be a poor relative, or the client of an agent who handles “$12,000 a week directors.”

Swanson told me that according to a recent ruling, a client does not have to prove that an agent has failed to give satisfactory service in order to terminate his contract. It seems that I have the right simply to notify Berg-Allenberg that I wish to terminate it and then it will be up to them to appeal to a labor board for a decision, if they wish. It would then be up to them to prove that they had given me valuable services and advanced my career. If they can prove it, I would have to pay them their commissions for the remainder of the contract. If they cannot prove it, I do not have to pay. In either case, I have the right to dismiss them and be represented by someone else.

I am enclosing a copy of my contract with them. After you have studied all this, will you let me know what action you decide is best — whether you will notify Berg-Allenberg that I am through with them entirely and let them appeal to a labor board if they wish, or whether I should merely dismiss them but continue to pay them commissions for another year, when our contract expires, and for the remainder of the Hal Wallis contract, if I continue with the Hal Wallis contract. Whichever you decide, it will be agreeable to me. I am quite willing to pay Swanson an additional 5 per cent, if necessary.

I need your help particularly in the following problem: It is my impression that Phil Berg has not merely remained neutral during the whole period of my work at Warner Bros., that is, did not merely neglect to do anything for me, but has been working actively against me. I have no complete factual proof of that, but it is an impression and a very uncomfortable one. Therefore, when I leave Berg-Allenberg, he may attempt some form of malicious action against me or against my interests in the picture, such as creating antagonism toward me in the minds of Jack Warner or other studio executives with whom he may have influence. So I would like to ask you to use your influence on Berg and Allenberg, in whatever way you find it possible, to prevent such actions. I know that such matters as personal malice are beyond anyone’s control, but I think that Berg-Allenberg would be afraid to antagonize you and would be more considerate or cautious in their attitude toward me, if they knew that you are watching the situation personally and intend to protect me.

I would like the notice to Berg-Allenberg to come from you for two reasons: First, to impress upon them the fact that I am primarily your client, not theirs. Second, because they might agree to relinquish the contract without any further nastiness. Also, I would like to have your moral support in this. I feel very indignant at their attitude, and I feel very hurt.

Please let me know what procedure you decide is best to set me free of them, before you notify them officially. If you ask them for their side of the story, as of course you should, please ask them to be as specific as I was.

Forgive me if this is so long, but I wanted to tell you everything, and I wanted to have a complete record of the whole matter for the future. It has taken me a week to write this letter. If it makes hard reading, you can imagine how hard it was for me to live through all this.

On October 1, 1948, Collins responded to Rand with a basically non-committal letter regarding her dispute with Berg-Allenberg. He confirmed that she had no legal right to a final say, adding that “it comes down to what commitment, moral or otherwise, may have been made to you in the course of the past few months. I have every confidence that your estimate of what has happened is factually correct. On the other hand, when Allenberg was recently in New York he insisted to me that they had done a very fine job for you at the studio. At this point, however, it doesn’t seem to me to matter at all who is right and who is wrong. You are dissatisfied and want to quit. Therefore, the sole question is how best to do it.” On October 20, Rand wrote to Collins, asking him to cancel her contract with Berg-Allenberg. (The courtroom scene was shot exactly as Rand wrote it, and it appeared that it would be released as she wrote it, but as it happened one line was cut from the end of Roark’s speech: “I came here to say that I am a man who does not exist for others.”13)

To Mario Profili (September 12, 1948)

Profili, vice consul of Italy, was a representative of the Federated Italo-Americans, an umbrella organization that united many clubs and societies supporting the Italian heritage in Southern California.

My dear Mr. Profili:

This is in response to your request for my permission to show the Scalera film based upon my book — WE THE LIVING in connection with the Columbus Day celebration.

I am very happy, of course, to cooperate in this celebration in every way possible; however, the picture contains certain dialogue which is not contained in my book and to which I cannot subscribe. In fact it is my position that these particular parts of the picture reflect unfavorably upon my book and injure my professional reputation.

However, for the sole purpose of assisting in the patriotic celebration on Columbus Day I shall make no objection to the showing of the Scalera picture provided it is clearly understood that I am not responsible for such dialogue as deviates from my book. Accordingly, I shall be glad to grant your request on the following conditions: that you engage a film cutter who will, under my direction, cut out of the picture the passages of dialogue which I find most objectionable; and further — in order to cover such lesser lines of dialogue as may be hard to eliminate — that before the picture is shown an announcement be made to the audience to the effect that the film was made in Italy during the war under conditions which did not permit me to consult with the producer or approve certain dialogue of which I am not the author; that by giving my permission for the showing I do not necessarily adopt or approve any lines which do not appear in the book entitled WE THE LIVING and that I reserve all legal rights which arise out of the use of the book by the producer of the picture.

I regret that I cannot release this picture without these stipulations and I trust that the required announcement can be made without great inconvenience.

Of course, you understand that I do not own the film itself and that it will be necessary for you to obtain authorization from the owner before it can be screened.

Although the event was planned as part of a Columbus Day celebration, Rand wrote to Profili almost five months later regarding changes in the statement to be read to the audience “at both performances.” If the screenings actually took place, Rand apparently did not attend, as there is no relevant entry in her daily calendars for 1948 or 1949.

To Gerald Loeb (January 8, 1949)

Gerald Loeb (1899–1974) was a founding partner of E.F. Hutton and Co. and a friend of Frank Lloyd Wright. Rand and Loeb had a lengthy correspondence between 1943 and 1949, during which period her daily calendars list numerous meetings and dinners with Loeb.

Dear Gerald:

This is just a brief note to let you know the big news: We had a preview of THE FOUNTAINHEAD day before yesterday, January 6 — and it was a triumph. Everybody present told me that it was the most sensational preview they had ever attended. The picture went over so well that Jack Warner did not make a single cut or change — and the final negative is being made right now. I don’t want to boast about all the details — I hope you will hear it from Warners themselves. As far as my opinion is concerned, the picture is magnificent.

With the best regards from both of us to both of you,

That was Rand at her most enthusiastic about the film. By the next year, her high opinion had waned: in a letter to a friend, she allowed that neither the casting or direction was “ideal,” but having her script shot verbatim was “a miracle.” Ten years later, in her biographical interviews, she said that although she liked the script, she “disliked the picture enormously, disliked everything about it,” criticizing the acting, the pacing and particularly the directing — she described director King Vidor as “a cheap, naturalistic mediocrity, and totally wrong for this job.”

Endnotes

- A few typographical errors and outmoded typing styles in these letters have been corrected without notation.

- The editor of Letters of Ayn Rand, Michael Berliner, notes that she often expressed to others her dislike of Southern California — the geography, the people, the lifestyle and even the weather. “When I told her in 1969 that I had accepted a university faculty position in Los Angeles, she was sympathetic,” he says. “When I told her that I was happy to be moving there and liked Los Angeles, she was aghast.”

- In her 1960–61 biographical interviews, Rand described Berner’s efforts at this arbitration hearing as “brilliant,” explaining: “. . . [I]t seemed that Woods had, apparently, faked some correspondence between himself and [Woods’s colleague, writer Louis] Weitzenkorn, because Pinkie could prove, by the way certain papers were folded that they were written at different times and they didn’t fit in the same envelopes, and Woods claimed they had arrived together. And I don’t even remember what it was; all I remember is that he caught him on the kind of tricks that you usually see in the movies, you know, proving that these papers were folded wrong and it was not the same correspondence, or something like that, something semi-criminal. [Berner] had a very calm, well-bred manner, which was just faintly sarcastic enough when necessary, in addressing Woods, and I think antagonized Woods enormously, deliberately — and deservedly. But he conducted himself well. He was, in effect, a good trial man.”

- Love Letters (1945), starring Joseph Cotten and Jennifer Jones.

- Photographs of this house, built in 1935 for filmmaker Joseph von Sternberg, are available at this link.

- Melville Cane, one of Berner’s partners in the law firm of Ernst, Cane & Berner.

- After World War II, the victorious Allies exercised control over the defeated Axis nations through Allied Commissions.

- The first paragraph of this letter was previously published in Letters of Ayn Rand on page 280.

- An Italian edition of The Fountainhead was subsequently published by Baldini and Castoldi.

- See Letters of Ayn Rand for several letters (indexed under “Strakow”) detailing Rand’s efforts in this regard.

- H. N. Swanson was Rand’s Hollywood agent from 1948 until 1952.

- This was an informal name for the Production Code Administration, Hollywood’s agency of self-censorship established in 1934.

- Jeff Britting, “Adapting The Fountainhead to Film,” in Robert Mayhew, ed, Essays on Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead” (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007), 115 n. 103.