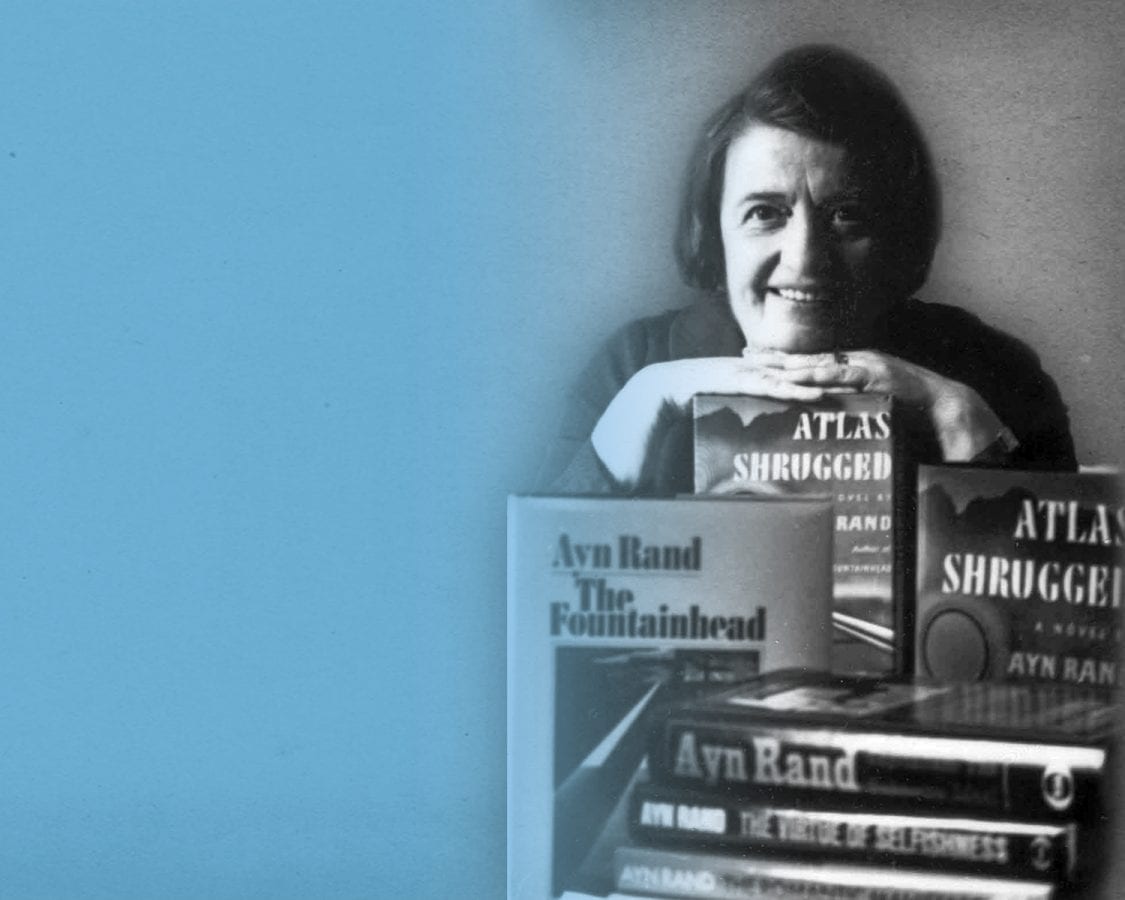

Ayn Rand Letters: Personal (1938 – 1950)

This is the fourth and final installment of previously unpublished Ayn Rand letters selected by Michael S. Berliner, editor of Letters of Ayn Rand. A total of forty letters have been divided into four groups for publication, according to general subject matter: Hollywood, novels, nonfiction (including political activism), and more personal correspondence.

“While recently writing the complete finding aid to the Ayn Rand Papers, I noted some interesting letters that I hadn’t selected for the Letters book,” Berliner says. “Now, more than twenty years later, these letters struck me as meriting a wider audience. These unpublished letters were selected because of their insight into some particular topic or some aspect of Ayn Rand’s life, or, more often, as further evidence of how her mind worked on a variety of matters.

“I’d always been impressed by the care she took with non-philosophical issues and relatively trivial matters, and this mind-set comes across in virtually all of her correspondence. For a variety of reasons, she was not a ‘casual’ letter writer but always took great care to write with great precision on matters that today are usually relegated to a quick, unpunctuated tweet. For an explanation of her non-casual approach, see my preface to Letters of Ayn Rand on page xvi.”

This fourth installment of unpublished material contains six letters addressed to the following individuals on the dates listed:

- Ethel Boileau (June 21, 1938)

- Leonard Read (November 30, 1945)

- Lynda Lynneberg (February 21, 1948)

- Hal Wallis (January 6, 1950)

- Lorine Pruette (April 28, 1950)

- Archibald Ogden (August 25, 1950)

What follows is the text of each letter, accompanied by remarks from Berliner (always in italics) supplying necessary context.1

To Ethel Boileau (June 21, 1938)

Lady Ethel Boileau (1881–1942) was an English novelist, best known for Clansmen and Ballade in G Minor. Her correspondence with Rand began in 1936, when she wrote a glowing homage to We the Living after her American publisher had sent her a copy. After Rand read Clansmen in 1936, she wrote to Boileau that her “descriptions are so lovely that they have made me, an Americanized Russian, experience a feeling of patriotism toward Scotland. Your book makes me believe that Scotland is a country of strong individuals and, as such, she has all my sympathy and admiration.” The letter below is a rare instance of Rand commenting about World War II.

Dear Lady Boileau,

Thank you so much for your letter. I was very sorry to hear that you have not been well, and I do hope that you have recovered completely. I am so happy to have met you and am looking forward to the time when you may come to American for another visit.2

However, looking at the picture of your charming house, I suspect that you may not be inclined to leave it often. I am sure that I should not. It has such a magnificent air of old Europe. I feel somewhat wistful as I say this, for the thought of Europe at present gives me a great deal of anxiety. I can well understand your feeling about it. I should not, perhaps, allow myself a definite opinion of the policy of a country which I do not know thoroughly, but I cannot help feeling a great sympathy for Premier Chamberlain. The least co-operation any European country has with Soviet Russia — the greater are the chances of saving Europe from another catastrophe. I am convinced that the major forces preparing for a general world conflict originate in Russia. I can only hope that the propaganda by the Soviet “United Front” will be defeated in England. It is being defeated here, or so it seems at present. The wave of Red public opinion appears to be ebbing quite definitely in New York, where it has always been at its strongest. I feel relieved for the first time in years.

I do hope that you have begun your next book. And I shall be waiting impatiently for the time when you resume the story of the Mallory family. The point at which you left them in “Ballade in G-minor” makes it unfair to keep your readers waiting too long. It will be interesting to see what happens to Colin now.

I am sending you a copy of “Anthem,” my new novel which I mentioned to you. It came out in England about a month ago, I believe. But there has been a delay in my receiving the copies here and they did not arrive until a few days ago. Incidentally, the clippings of reviews have been lost on their way to me from England and I have no idea how the book was received.3 I have been promised duplicates and am now waiting for them. I shall be most anxious to hear your opinion of this book.4

At present, I am working on my next novel — the very big one about American architects. For the last few months I have been wracking my brain and nerves upon the preliminary outline. It is always the hardest part of the work for me — and my particular kind of torture. Now it is done, finished, every chapter outlined—and there are eighty of them at present! The actual writing of it is now before me, but I would rather write ten chapters than plan one. So the worst of it is over.

I received a very charming letter from Princess [Marina] Chavchavadze. As she did not tell me her address, would you be so kind as to give her for me my regards and my gratitude for the kind things she said about “We the Living.”

My husband joins me in sending you our best wishes.

To Leonard Read (November 30, 1945)

Leonard Read (1898–1983) was the founder of the Foundation for Economic Education. He was general manager of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce when Rand met him (via Isabel Paterson). The meeting took place in late 1943, when Read arranged a dinner for some pro-free enterprisers (mostly businessmen and attorneys) to meet Rand. In her biographical interviews, she reported that at the dinner “were twelve men, and I was the thirteenth, and the only woman. And we had a round table. And I met all the best conservatives there.” That seems to be a major impetus in Rand’s involvement with leaders of the “conservative” movement, a movement with which she eventually became disillusioned. In 1961, she commented that Read “was much more — how would I put it — intellectual and idealistic then than he is now. And, for a long time, both Isabel Paterson and I regarded him as the hopeful rising conservative of a practical, but intellectual kind. Which he lost totally once he went on his own.” Based on her daily calendars, her last socializing with Read seems to have been in 1951.

Dear Leonard:

Thank you for your letter. I am sorry that we didn’t have a chance to see you again before we left New York. If you come to the Coast again on one of your flying trips, do let us know and try to give us an evening if possible.

I didn’t have any extra copies of “The Fountainhead,” but I got one here in town, have autographed it and am sending it to your friends, as you requested. The enclosed buck is your change — you sent four dollars and the book cost only $3.00. The postage is something like 7 cents, so I’ll contribute that.

Thanks for the copy of Rose Wilder Lane’s book reviews. I appreciate very much her note on my book. Yes, she has done a very good job on Bastiat and she is an excellent reviewer.

You asked where to get “We the Living.” It’s out of print. I have only my own single copy left. But I’m sending you, under separate cover, a copy of the English edition. It’s the same as the American edition, except that my love scenes have been slightly censored, unfortunately.

Let me know if anything of interest is happening among our conservatives. It seemed awfully dull and disappointing to me, what I saw of their activities in New York.

My trip east has done me a lot of good — I feel rested and reconciled to California for a while. But I’ll always miss New York and I’ll always love it better than any place on earth.

With best regards from both of us,

Sincerely,

On December 28, 1945, Read replied, “I am only partly through [We the Living], but what a book!”

To Linda Lynneberg (February 21, 1948)

Rand met Linda Lynneberg when she came to work under Rand as a volunteer researcher during Wendell Willkie’s 1940 presidential campaign. They became friends, and Rand employed her as a typist in the early 1950s. In her biographical interviews, Rand said that Lynneberg got converted to Catholicism under Isabel Paterson’s influence and was “almost wrecked by it.” Nevertheless, Rand was still socializing with Lynneberg as late as 1975.

Dear Linda:

You are quite right, if I don’t write letters it’s because the book has been going along wonderfully. But thank you for your letters and for all the clippings and information about oil. I haven’t read all the booklets yet, but I believe it is just the kind of stuff I need.

I was very startled to hear about the existence of a Miss Ann Taggart. Now all you have to do is find Mr. Wesley Mouch for me. (I am afraid, however, that the Mouches are all around us everywhere.)

I hope you like the cigarette holder. I couldn’t get you a silver one in this shape. The silver ones were shorter and stubbier; I think they are intended for men. So I decided to buy the same kind I had. I hope the color will remind you of me.

No special news about us, except that I have been working on the novel very well indeed. I had to be interrupted this week with a lot of other business, such as the Italian movie of WE THE LIVING, which I ran for some of my friends and for which I am still negotiating a settlement. Also, you may have read in the papers that Warner Bros. are starting now on the production of THE FOUNTAINHEAD. Nobody is set for the cast yet — except Gary Cooper. Do you remember our meeting with him? I am certainly delighted about this, since of all the big name stars, he is my choice for Roark. The director is to be King Vidor. I have not met him yet, but I understand he is a conservative, at least he was a member of M.P.A. at one time, so I’m glad about that.

I have taken some time off to write to Pat and couldn’t do it in less than five single-spaced pages. I had a wonderful letter from her in answer, and believe it or not, I answered back, too. When Pat is in a good mood, she is like quicksand, completely irresistible, so maybe I shall become a good correspondent.

We had some terribly cold nights, and our moats were frozen solid, but I think spring is coming now. I am looking for your Texas bluebonnets, but so far they have not appeared yet.

The enclosed ad was discovered by Frank in a Valley paper. He thought you’d be pleased to see it. I think your sense of humor and his are very much alike.

I hope that your business will pick up and that you’ll feel better than you sounded in your last letter. I enjoyed your visit here so much that I hope you will come back before you return to New York. Incidentally, Teresa is back with us and everything is going along wonderfully, and the house is really comfortable and well run now.

Love from both of us,

P.S. I am sending this to your Tulsa address because I could not decipher the one you gave me for Oklahoma City. Your handwriting is as bad as mine. I hope this reaches you.

To Hal Wallis (January 6, 1950)

From 1944 to 1949, Rand was a screenwriter for Hal Wallis (1898–1986), producer of Casablanca and many other famous films. Under Wallis, she wrote the screenplay for Love Letters (1945) and unproduced scripts of “The Crying Sisters” and “House of Mist.” Although she generally liked working with Wallis she became disappointed with the stories he was producing and disappointed in him personally when she discovered that their project for a film about the atom bomb (working title “Top Secret”) was merely a ploy by Wallis for him to sell the story rights to MGM, which was producing The Beginning or the End (1947). However, although she considered him a second-hander (in the Peter Keating sense) as a producer, she said in her biographical interviews in 1961 that “he was a very nice person, as a person, pleasant to deal with,” and they continued on friendly relations.

Dear Boss:

This is to thank you formally for your lovely present. It was such a nice gesture on your part that you broke my heart with kindness — a thing you have always known how to do. I was happy to know that you still remembered me. I hope you know that I will always think of you with respect and admiration.

Thank you for the past and the present, and all my best wishes to you for a Happy New Year.

Sincerely,

To Lorine Pruette (April 28, 1950)

Lorine Pruette (1896–1977) was a well-known writer, psychoanalyst and feminist. In 1943, she reviewed The Fountainhead for the New York Times, a review that Rand was especially grateful for. In her biographical interviews, Rand commented: “That really saved my universe in that period. I expected nothing like that from the Times. And it’s the only intelligent review I have really had in my whole career as far as novels are concerned.”

Dear Lorine:

Thank you for your post card. I can’t tell you how homesick it made me for New York and for the nice evening we spent with you.

I don’t know yet when I will be back East, as I am deep in work on my new novel. It’s going along wonderfully and I am very happy with it. Your rose quartz is here on my desk as reminder and inspiration.

What are you doing? Have you been writing any articles or reviews? What has happened to your proposed article about me — or is it a subject the magazines are afraid of at present? Did you ever meet Archie Ogden? He has just gone back into the publishing business and is now editor of Appleton-Century. Do let me hear from you when you have the time.

With love from both of us.

This is the last correspondence between Rand and Pruette in the Ayn Rand Archives, but Rand moved permanently to New York City in 1951, and her daily calendars show numerous dinners with Pruette from 1951 through 1958.

To Archibald Ogden (August 25, 1950)

Archibald Ogden was Rand’s editor on The Fountainhead. His almost legendary status among Objectivists was secured when he put his job on the line, telling his employer, Bobbs-Merrill, that if The Fountainhead wasn’t the book for them, then he wasn’t the editor for them.

Archie darling:

Thank you for your letter. It is I who have to ask you to forgive me for my long delay in answering, this time. I think you know that the only valid reason which could have prevented me from writing you sooner was the work on my novel. I am just approaching the end of Part I, and I did not dare interrupt myself while I had the whole world crashing — in the novel, I mean.

I hope that you won’t be let down by hearing that I am only at the end of Part I. As you know, my speed of writing always accelerates as I approach the climax of a story, so I don’t think that it will be too long now before I finish the whole book — but I won’t even make a guess at the date, in order not to disappoint you later. Part I, however, is about two-thirds of the whole book in length. I can’t tell you how much I wish I could show you what I have written since I saw you last. I know you would be pleased. Be patient with me for taking such a long time — it is really going to be worth the waiting. As for me, I am simply crazy about the story and I am very happy with it.

Thank you for the things you said about me in your letter, about my manner of integrating ideas into a story. You and I are probably the only two people in the literary profession who understand fully how difficult and how important this is. Your remarks on the subject were one more proof to me, though I didn’t need any, that you are the one and only editor for me. I hope that sooner or later you will be my official editor in fact. You will always be my personal one in spirit.

I was delighted to hear that you are happy at being back in the publishing business. This supports what I had always expected. You were wasting your talent on the movies, and publishing is where you belong.

Who is the young man you mention in your letter, the one who admires THE FOUNTAINHEAD and is writing a novel about the steel business? Is his name Thaddeus Ashby? I strongly suspect that it is, and if so, I must warn you to be careful. Ashby is a boy whom I met here some years ago and who professed a great admiration for THE FOUNTAINHEAD. I have not been in touch with him for a long time, but I have heard that he had gone to work in a steel mill and was writing a novel. He is a young man who professes all the ideals of Roark, but practices the methods of Peter Keating, or worse. When I met him, he told me a great many things about himself, all of which turned out to be untrue. For instance, he said that he had just come from the Pacific where he had been an aviator and had been shot down twice. Later, I learned that he had been in aviation training during the war, but had never left this country. If he gave you the impression that he learned about you and the history of THE FOUNTAINHEAD in some mysterious way — then that is a typical example of his behavior. He heard all about you and the history of THE FOUNTAINHEAD — from me. If he did not tell you so, it is probably because he knows that I would not give him a good recommendation, and that he had no right to approach you in that manner, to use — without my knowledge or approval — any information which he obtained from me. I do not want to be indirectly responsible for some fraud which he might possibly have in mind against you. My impression of him is that he is intelligent, but I have my doubts about his literary talent. It is possible that he may develop, but I would be inclined to doubt whether he is yet ready to produce a good novel. If you find that you want to deal with him, I would warn you to take every legal precaution that might be necessary. For instance, I would not advise you to give him any advance or commitment on unfinished work.

Let me know the name of the novel which is your own choice on your fall list — I would like to read it. No, do not send me a free copy — I want to have the privilege of buying and supporting any novel which is your choice. If I were a collectivist, I would be jealous of any writer you select, but since I am an individualist who believes that there is no clash of interest among people and that any talent is a help, not a threat, to another talent, I will wish you to discover a whole list of your own writers, all of them good. In fact, I wish you a whole harem of them. But, of course, being selfish, I want to be the wife No. 1. And being conceited, I am not afraid of competition for that title.

With best regards to both of you from both of us — and all my love to you,

Rand and Ogden remained friends until 1967, when Ogden submitted an introduction to the novel’s 25th anniversary edition, an introduction that Rand considered inappropriate. Her lengthy letter to him (pages 643–46 in Letters of Ayn Rand) concluded, “I must tell you frankly that I do not think it will be possible for you to write an Introduction which would be acceptable to me . . . . I will not attempt to tell you how sad and painful this is for me.”

Endnotes

- A few typographical errors and outmoded typewriting styles in these letters have been corrected without notation.

- In his February 21, 1938, “The First Reader” column in the New York World-Telegram, Harry Hansen notes that on February 17, Lady Boileau attended a “cocktail party given by Ayn Rand” at Town Hall in New York City.

- The reviews were generally positive. For details, see the chapter “Reviews of Anthem” in Essays on Ayn Rand’s “Anthem,” edited by Robert Mayhew.

- On September 29, 1938 (the day of the Munich Agreement that ceded the Sudetenland to Germany), Boileau wrote Rand that Anthem is “an allegory of which the world of today might well heed.”