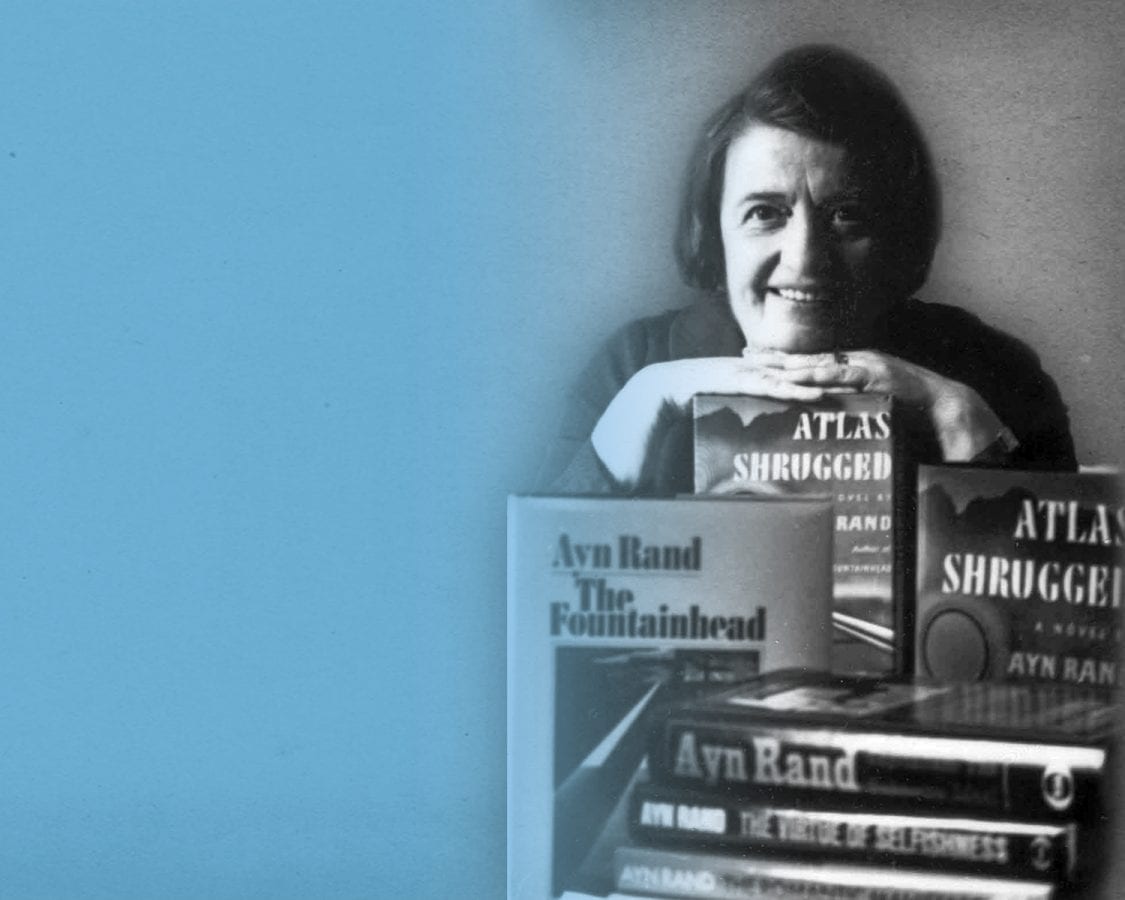

Ayn Rand Letters: Fiction (1935 – 1980)

This is the second of four installments featuring previously unpublished Ayn Rand letters selected by Michael S. Berliner, editor of Letters of Ayn Rand. A total of forty letters have been divided into four groups for publication, according to general subject matter: Hollywood, fiction, nonfiction (including political activism), and more personal correspondence.

“While recently writing the complete finding aid to the Ayn Rand Papers, I noted some interesting letters that I hadn’t selected for the Letters book,” Berliner says. “Now, more than twenty years later, these letters struck me as meriting a wider audience. These unpublished letters were selected because of their insight into some particular topic or some aspect of Ayn Rand’s life, or, more often, as further evidence of how her mind worked on a variety of matters.

“I’d always been impressed by the care she took with non-philosophical issues and relatively trivial matters, and this mind-set comes across in virtually all of her correspondence. For a variety of reasons, she was not a ‘casual’ letter writer but always took great care to write with great precision on matters that today are usually relegated to a quick, unpunctuated tweet. For an explanation of her non-casual approach, see my preface to Letters of Ayn Rand on page xvi.”

This second group of unpublished letters contains fourteen letters addressed to the following individuals on the dates listed:

- A. H. Woods (October 17, 1935)

- Newman Flower (June 3, 1936)

- Channing Pollock (December 10, 1941)

- D. L. Chambers (February 14, 1944)

- Alan Collins (February 15, 1946)

- Ann Watkins (March 29, 1946)

- Ruth Meilandt (July 11, 1946)

- Ruth Meilandt (August 5, 1946)

- Alan Collins (August 6, 1946)

- Gerald Loeb (July 31, 1947)

- John L. B. Williams (December 13, 1947)

- Pincus Berner (April 3, 1948)

- Rosemary York (September 4, 1948)

- Jeannie Cornuelle (April 19, 1980)

What follows is an introduction by Berliner to this installment, followed by the text of each letter with remarks from Berliner (always in italics) supplying necessary context.1

Please note:

- The letters published in this series are letters and not formal statements of Ayn Rand’s philosophic positions written for publication. Consequently, they should not be taken as definitive, and the reader should not exaggerate the importance of (a) possible ambiguities caused by her using informal rather than more precise language or (b) seeming conflicts with her published views. In all cases, her published statements are definitive.

- Photos, images, captions and footnotes are not part of Ayn Rand’s letters unless otherwise noted.

- These letters, owned by Leonard Peikoff, are part of Ayn Rand Papers collection. Their reproduction here is courtesy of the Ayn Rand Archives. The Ayn Rand Institute extends its warm appreciation to Leonard Peikoff and the Ayn Rand Archives, and also to Clarisa M. Randazzo, the volunteer who carefully transcribed all of the newly published Ayn Rand letters from the originals.

The following fourteen letters concern Ayn Rand’s fiction output. Spread over forty-five years, these are among many dozens of her letters that illustrate the care she took with all aspects of her writing career — from advertising to cover art, from theatrical casting to book distribution and legal contracts.

To A. H. Woods (October 17, 1935)

H. (Al) Woods (1870–1951) was the producer of Night of January 16th on Broadway. Of his 142 Broadway plays, January 16th was his 136th. The first production of Ayn Rand’s play was in 1934 in Hollywood, under the title Woman on Trial, and was produced by E. E. Clive and starred Barbara Bedford (#13 on Rand’s Soviet-era list of favorite actresses). The play was then purchased by Woods and had a 29-week run on Broadway beginning September 16, 1935, one month before the letter below was written. Although the play provided significant income and induced Rand and her husband to move to New York City for the first time, it was not a pleasurable experience for her, because it was beset by actors who didn’t understand their lines, constant disputes with Woods over script and casting changes, pointless experiments and, finally, legal arbitration (won by Rand) over unpaid royalties. One such casting dispute is the subject of this letter to Woods. Rand was partly responding to an October 15 letter from Woods, in which he argued that Bakewell was good for the part, adding that “my judgment might be just a little bit better than yours.”

Dear Mr. Woods,

In reply to your letter of October 15th, I must state that I find it impossible to agree to the choice of Mr. William Bakewell for the part of “Guts Regan.” Since you went to some length in explaining your reasons for this choice, I must explain in detail my reasons for refusing to approve Mr. Bakewell in that part.

As I have stated in my letter of October 14th, I find Mr. Bakewell much too young for the part. Mr. Bakewell’s personality is that of a meek, harmless, wholesome high-school child and this is the type of part which he has played on the screen. His personality would not allow him to play even the part of a small-time gangster, merely a member of a gang. But when it comes to playing a man who, as “Guts Regan,” is the head of a gang and, more than that, the head of the underworld in New York City, the Public Enemy #1 with a price of $25,000 on his head — well, you must grant me that it becomes dangerously near to being ludicrous. Not only is Mr. Bakewell’s personality unsuited to the part, but he actually looks about eighteen years old. It may not be his real age, but that is the impression he gives on the stage. How a man under twenty could be accepted as an underworld dictator is more than I can understand.

You quote the instance of Miss Nolan and remind me that she, too, was too young for her part. Aside from the fact that this is quite irrelevant and that I shall discuss it later in fuller detail, I would like to remind you at this point that Miss Nolan does not look her age. I have heard people who saw the play voice the opinion that Miss Nolan was thirty. She is a good enough actress to conceal her youth. Unfortunately, Mr. Bakewell looks younger than his probable age, and the juvenile quality of his personality is carried into his voice, his stage manner and his whole performance, which I found thoroughly unsatisfactory. Furthermore, while we could “fake” on Miss Nolan’s age by omitting from the play the fact that she had been employed as a secretary for ten years, there is no possible way to cover up, soften or explain how a boy of eighteen became the leader of the underworld and was entrusted with the responsibility of assisting the foremost world financier in his most dangerous plot.

You said in your letter that you want “a man with some refinement and romance.” I can see absolutely no romantic quality in Mr. Bakewell and he has never, to my knowledge, played romantic characters on the screen. He has played juveniles of the “young brother” or “son” type, not lovers. You claim that Mr. Bakewell’s picture work may be an asset to him on the stage. I find that it will be a detriment, since he has always been associated in the public mind with the type of part I have described above, if we are to suppose that his name is sufficiently known to the public. However, I am inclined to think that any following he may have is hardly prominent enough to be considered as a box office attraction.

I may remind you that the Minimum Basic Agreement calls for “a first class production with a first class cast.” Mr. Bakewell has, evidently, never appeared on the professional stage, since he has just joined the Actors’ Equity Association, as I was informed. Being a beginner, as far as the stage is concerned, he can hardly be considered as a first-class stage actor.

You complain in your letter that I did not notify you of my disapproval for Mr. Bakewell before his seven days try-out period had elapsed. I have had no notice of any kind when Mr. Bakewell started rehearsing. I do not know now the date on which he was engaged. I do hope that this notice was not omitted intentionally to provide for an emergency such as this. The rehearsal which I attended with you and to which you refer in your letter of October 15th, took place not “about a week ago,” as you state, but on Friday, October 11th. I had not been notified even about that rehearsal, but happened to see, by chance, an announcement of it on the wall back stage, at the Ambassador Theater. You left that rehearsal before it was finished and I had no chance to speak you, nor did you ask me for my opinion. However, on the following day, Saturday, October 12th, I telephoned to you at your office and tried to make an appointment to see you. You refused the appointment and asked me what I wanted to see you about. When I stated that I wanted to discuss the cast, you answered that the cast pleased you, which was all that was necessary. I attempted to explain that I wanted to discuss Mr. Bakewell and give you my opinion of his performance. You hung up the receiver in the middle of my sentence without letting me finish my statement. You have yourself mentioned this episode to a person who has since repeated it before witnesses. However, I am sure that you will not attempt to deny this. On Monday, October 14th, I sent you a letter by messenger in order to avoid delay, stating my formal complaint. As you see, I have tried my best to settle the matter as quickly as possible.

May I also remind you that you have repeated persistently and on numerous occasions your claim that I had no say whatever about the casting of my play, that you would cast anyone you wished whether such persons met with my approval or not. On the few occasions when you agreed to discuss the cast with me, it was done after many most unpleasant arguments. May I remind you that, foreseeing a situation such as this, I came to your office at the time when you were first casting my play, before rehearsals started, and brought to your attention the fact that Mr. Pidgeon had been signed for another play and would not be able to remain with our company longer than the first few weeks. I suggested then that we agree on an actor to replace Mr. Pidgeon, in order not to hold up the play later, when Mr. Pidgeon would be forced to leave. Do I have to remind you that your answer was much less than polite and that you gave me to understand I was transgressing my rights as an author? This is in spite of the fact that our contract states clearly my right to approve of any and all members of the cast.

You have held to the letter of that contract and I have had to comply, no matter how difficult it has been at times. May I ask how you intend me to be bound by a contract while you do not intend to be bound by it? You must realize that if you allow an actor to appear on the stage in my play, disregarding my formal objection to that actor, you will break the Minimum Basic Agreement which we have both signed.

Quoting from your letter, I find that you make the following statement: “It is strange that you should pick out two people, Mr. Shayne and Mr. Conway, and suggest them for the part. I suppose those are the only two actors you know, owing to the fact that you have seen them both.” I do not see just what can be strange about it nor what does the fact of how many actors I had seen have to do with the case. I suggested Mr. Conway and Mr. Shayne because they are the only two actors I know who are familiar with the part and who could step into the play after one rehearsal. I believe I made this clear in my letter when I suggested them.

You state that you are sure Mr. Bakewell “will give a better performance than either of the two gentlemen you named.” How can you know it when, to my knowledge, you have never given either Mr. Conway or Mr. Shayne a chance to read the part for you? On the other hand, I have seen Mr. Bakewell rehearse the part and I have seen Mr. Conway play it in Hollywood, so I have the grounds necessary to make a comparison. I do not believe I am exaggerating when I say that Mr. Conway’s performance was so superior to Mr. Bakewell’s that there can be no comparison.

As to Mr. Shayne, I have never said that he was the only weak link in our cast, as you claim I have. It is true that I have never been pleased with his performance in the part of the Defense Attorney, for the main reason that I found him too young for that part. If you remember, it was my first objection to him when I first met him as a prospective “Defense Attorney.” During the rehearsals that followed, I expressed my opinion to you and to Mr. Hayden, on several occasions, stating that I feared Mr. Shayne would not be satisfactory in the part. You assured me most emphatically that Mr. Shayne would improve with rehearsing and that he would be excellent in actual performance. You told me that you had seen him in another play and that he had been magnificent. Owing only to the fact that I trusted your judgment, I made no formal, definite objection and allowed Mr. Shayne to remain in the part. You know the consequences. You found it necessary to dismiss Mr. Shayne and replace him with Mr. Tucker, without any suggestion from me.

If you find that Mr. Shayne does not have weight enough for the part of “Guts Regan,” how can you possibly consider that Mr. Bakewell has it? Of the two, doesn’t Mr. Shayne have the infinitely stronger, more forceful, more mature personality? I am still convinced that Mr. Shayne is a good actor in a part to which he is suited, and your own opinion of his performance in another play supports my conviction. I believe that he could be satisfactory in the part of “Guts Regan,” and I do think that it would be worthwhile at least to allow him a reading of that part, if you are sincerely anxious to find an actor to replace Mr. Pidgeon on short notice, an actor who would be acceptable to both of us. The same consideration applies to Mr. Conway.

Coming back to the subject of Miss Nolan, I must state that I was surprised by your presentation of the facts in your letter. You claim that I wanted her out of the cast. I had never wanted that and the best proof of it is that Miss Nolan is in the cast and that I never made any formal complaint against her, as I am doing now against Mr. Bakewell. During the first week of rehearsals, I did feel dubious about Miss Nolan’s ability to handle the part of “Karen Andre,” but I told you, as well as Mr. Hayden, that I was willing to let her go on with the rehearsals, since I felt that she showed great promise and I saw a definite chance of her coming up to our expectations, with proper coaching. This she did accomplish and I was one of the first to express my enthusiasm for her excellent work. As you know, I was not the only one to doubt her ability to handle the part, at first. You yourself have told me that she was not adequate during her first rehearsals; and Mr. Shubert was ready to have her replaced, since he brought several prominent actresses to witness the rehearsals, for the purpose of offering them the part of “Karen Andre.” Had I had a definite objection against Miss Nolan, I could have taken advantage of the situation then and insisted on her dismissal. I did not to do it, because I felt that she would improve, as I had stated repeatedly. While Miss Nolan may be too young for her part in real life, she does not show it on the stage and I have not objected to her stage appearance. I cannot say this of Mr. Bakewell, since he does appear hopelessly boyish.

As to your statement that I can thank Miss Nolan for whatever success my play has had up to the present time, I do not think that you believe this yourself. I have seen no reviews to that effect nor have I heard anyone voice that opinion. Without casting any reflection on Miss Nolan’s excellent work, I must say that all the reviews attributed the possible success of my play to the idea of a jury drawn from the audience. The publicity stories which came from your own office have all stressed that jury angle and publicized it as the main novelty and attraction of the play. So why make unfair statements which lead us nowhere?

Referring to your letter further, I find that you mention and seem to resent my attitude toward Mr. Harland Tucker. I do not see what that can possibly have to do with the case. Furthermore, although I would not have selected Mr. Tucker as my idea of the type needed for the part of the Defense Attorney, I have not objected to his playing the part, since his acting is adequate. I do not recall discussing Mr. Tucker with any actors back stage and I am perfectly certain that I have never suggested him for the part of the “Doctor.”

And, finally, I do not doubt your ability to pick unknown talent nor the fact that you have discovered many great stars in the past. But, as you say in your letter, we can all make mistakes. If the casting of Mr. Shayne as the Defense Attorney was a mistake on your part, I am afraid that you are about commit a much graver mistake by allowing Mr. Bakewell to play “Guts Regan.” Mr. Shayne at his worst has never been as unsuited to the part of the “Defense Attorney” as Mr. Bakewell is to that of “Guts Regan.”

As you see, I have gone to great lengths in order to point out to you all the details of my complaint and to prove to you that this complaint is not unreasonable. I am very anxious to settle this matter in an amicable manner, if you will allow me to do so. However, your attitude on the question of casting has left me no choice but to demand an arbitration. I am sending today an application for arbitration on this question to the Dramatists’ Guild, along with a copy of this letter. You realize that if you allow Mr. Bakewell, over my objection, actually to perform in my play beginning Monday, October 21st, it may entitle me to claim a breach of our contract. I do hope that we can still avoid it.

If you can find another actor for the part of Regan, acceptable to both of us, please let me know so that the arbitration proceedings may be stopped. I hope that we will be able to agree on another actor, for we still have the time.

Sincerely yours,

On the same day as the letter above, Rand wrote to the Dramatists’ Guild requesting arbitration. But the next day, Rand withdrew her application for arbitration, stating that “Mr. Woods and I have reached an agreement.” The terms of that agreement are not known, but Bakewell continued to appear as “Guts” Regan until the play closed in April of 1936. Rand later commented: “I almost had an arbitration with him over a replacement for Walter Pidgeon during the last months or so of the play [during its preview in Philadelphia], when [Pidgeon] went to Hollywood. But it wasn’t worth it.” Because Pidgeon had the role of Regan in out-of-town tryouts and for the first month on Broadway, reviews of the play do not mention Bakewell. Bakewell’s reminiscences, Hollywood Be Thy Name, make no mention of the issue of his casting.

To Newman Flower (June 3, 1936)

Newman Flower (1879–1964) was the proprietor of the publishing house Cassell & Co., which published We the Living, Anthem and The Fountainhead in the United Kingdom. Flower is best known for publishing Winston Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples and The Second World War. After receiving a copy of the U.S. edition of We the Living, Flower wrote to Rand on April 14, 1936: “I think this is a magnificent piece of work, and one of the finest first novels I have ever read in my life . . . . I am looking forward to seeing you one of the best most successful novelists on Cassell’s list.” Rand’s letter below is in response to a May 11, 1936, letter from Flower in which his specific suggestions were preceded by a more general explanation: “I will be very grateful if you will make one or two modifications in the proofs which I enclose, or else allow the penciled alternations to stand. The reason is this: the principal book buyer in this country is Boot’s Library. In America one can be more frank in a book than here because, if there is too much frankness, Boot’s will not take the book. This means the loss of the biggest customer.”

Dear Mr. Flower,

Thank you for your letter and the suggestions of changes in the galleys of my book.

I am perfectly willing to make the changes suggested, for I consider the somewhat too frank love passages as the least important ones in the book and I certainly would not want to let them handicap the novel as a whole or detract any possible buyers from it.

I do approve of the changes made and I have marked them on each galley with my initials.

Primus stove

On gallery 51, I have no objection whatever to substituting “stove” for “Primus” if there is the slightest danger of a libel suit.

In regard to galley 63, your editor was quite correct in saying that a “Primus” is lighted with spirit first. That is the proper way to light it, but spirit was so expensive in Russia at the time that everyone had to use kerosene instead, which added to the discomfort of using a “Primus.” I have inserted a few words of explanation to that effect; if you consider it advisable you may keep the insertion in the text; if not — please omit it.

On galley 42, I made an additional cut of three lines which may be considered objectionable. You may keep the lines in, if you find it safe, or eliminate them if it is preferable.

On galley 39, in the most objectionable scene of the book, I cut out the entire ending of the scene. I think you will agree with me that it is better to do so. The only importance of the scene is the psychology of Kira’s surrender in a cold, tense, matter-of-fact manner, without the usual sentimental love-making. I have kept enough of the scene to suggest this. The rest — the description of physical details — is not really important. Particularly if the strongest lines are cut out of the last paragraphs, the remaining lines have very little meaning, since they do not even create a definite mood. So I think it is best to omit these last paragraphs entirely. It will be safer and the story as such will not suffer from the omission.

If you find any other passages that arouse doubt on the same grounds as the above, please let me know and I shall be glad to adjust them. Of course I will want to see the suggested changes before they are printed and I would appreciate it if you would send them to me in advance, as the ones we have made so far. I would also appreciate it very much if you would send me the galleys when they are ready, for there were a few mistakes in the American galleys, which were corrected later and which the proofreader may not be able to catch.

If I am free in September when the book comes out, I shall be delighted to come to London. Until then, please let me know if you need any further information or pictures of me for publicity. I am collecting all the reviews on my book which are still coming in and I shall send then to you in a few days.

With best wishes,

Sincerely yours,

To Channing Pollock (December 10, 1941)

Channing Pollock (1880–1946) was a successful Broadway writer, responsible for such shows as the Ziegfeld Follies of 1911, 1915 and 1921 and other plays, many of which were turned into films. In the early 1940s, he and Rand attempted to create what she called “The Individualist Organization” in the wake of the failed Wendell Willkie presidential campaign. In a previous letter to Rand (dated November 27, 1941), Pollock included a copy of his letter of the same date to Mrs. William Henry Hays, president of the Republican Club of New York City. In that letter, Pollock recommended Rand as a speaker, writing: “I have not heard Miss Rand speak in public, but if she can do so with any degree of the conviction and eloquence with which she speaks in private, and with which she writes, she should be one of the greatest orators of all time. I have never met anyone of more remarkable personality and individuality, or with a more burning conviction.”

Dear Mr. Pollock:

Thank you for the letter which you wrote about me to Mrs. Hays. I can only say that I shall try to deserve the recommendation you gave me. I have not heard from the Republican Club as yet, but if I should get that lecture it will not please me more than the things which you said about me.

Channing Pollock

Please forgive my delay in answering your letter. So many things have happened to me lately that I have been in a sort of whirlwind. The big event in my life is that I have just sold a novel to Bobbs-Merrill Company. It is an unfinished novel on which I have been working for a long time and which I could not finish for lack of funds. Bobbs-Merrill liked it well enough to give me an advance that will permit me to leave my job at Paramount and finish the novel. I cannot say what it means to me — to be able to return to creative writing again. I think you will understand. I am afraid I’m so happy that I’m a little dizzy. I signed the contract yesterday.

When you have the time, I should like very much to hear from you and to see you, if possible.

You asked my husband’s first name. It is Frank O’Connor.

He joins me in sending you our best regards,

Sincerely,

There is no record of Rand speaking to the Republican Club of New York City, but the collection of her daily calendars doesn’t begin until 1943.

To D. L. Chambers (February 14, 1944)

David Laurence Chambers was president of the publishing company Bobbs-Merrill when The Fountainhead was submitted to it in 1941. Archibald Ogden, one of the company’s editors, recommended the manuscript, but Chambers rejected it. Ogden then threatened to resign, writing: “If this is not the book for you, then I am not the editor for you.” Chambers relented, wiring Ogden: “Far be it from me to dampen such enthusiasm. Sign the contract.” In the letter below, Rand is responding to a letter from Chambers dated February 3, 1944, almost a year after the novel was published, reminding Rand of restrictions on paper quantities implemented by the War Production Board but reassuring her of “our ability to supply all orders.” Chambers’s letter also ties motion picture-induced sales to a projected paperback edition of the novel.

Dear Mr. Chambers:

Thank you for your letter of February 3rd. I am astonished that you did not understand me when I wrote about the effect of a motion picture on the sales of a novel. An important picture with a good publicity campaign gives a great boost to the sales of a novel in its regular edition. I refer you to the case of “King’s Row.”

I was and am interested only in the sale of the regular edition. I am not thinking of a popular reprint. It is much too soon for that. Of course “The Fountainhead” cannot be put out in a 25¢ Pocket Book type of edition. But if the picture helps to sell 100,000 copies of the regular edition, I will call that a big sale. A picture can do that and, in this case, I think it will.

There can be, of course, no question of paper difficulty about printing 100,000 copies of “The Fountainhead” when they become needed. Other publishers have printed 500,000 copies of books longer than mine.

I am concerned over this matter, because “The Fountainhead” was allowed to get out of print twice, last summer and fall, last time (in October) for three weeks. Each time, this happened at a crucial moment, when the demand for the books was growing, and each time the demand was killed. The worry and trouble which I was forced to take over the matter in October prevented me from working on “The Moral Basis of Individualism,” which would have been finished then but for this matter. I did not expect such a disastrous occurrence a second time.

Cover of Omnibook January 1944

I am counting on you to see that this does not happen again. I realize fully how it happened. It was due to the pessimism of Bobbs-Merrill, who handled the book over-cautiously, played for loss and did not expect good sales. When the sale came, they were caught short. I think we can still make up for it. But please remember the we must make up for it. I do not intend to have “The Fountainhead” as the victim of miscalculation.

War-conditions in the printing industry do not relieve you of the contractual obligation to keep my book in print in step with the demand. Since we know that everything is done slower now, we must make our calculations accordingly. It is merely a matter of ordering new printings earlier and in a larger quantity than would have been necessary in peace-time, when the exact date of delivery could be predicted.

I believe we are almost out of print now, unless you have reordered since I left New York. I am particularly concerned about the Literary Guild campaign which will help our sales. I do not want to see a break like that go to waste again. The same applies to the time when the motion picture will come out. I expect you to have the book in print, in step with and sufficiently ahead of the demand.

Referring to the last paragraph of your letter on January 28th — to the Omnibook2 matter — I must remind you that what you call a “fait accompli” was an accomplished breach of contract. Please do not expect me to accept any more breaches, of any nature, in the future.

As to “The Moral Basis of Individualism” I shall finish it as soon as I can, but I cannot give you a definite date until I have finished my work for Warner Brothers. Your suggestion that I “do something on the book each day” is entirely out of the question. First, I am not permitted to do it by my contract with Warner Brothers. Second, do you really think that a serious book on so difficult a subject can be written in snatches and in between times?

If you are concerned over the fact that the book will come out too long after the Reader’s Digest article3 — I believe I will get ten other articles out of it, to help us when the time comes. But we must finish the job on “The Fountainhead” properly, before we undertake the next one.

Sincerely yours,

In a four-page response on February 22, 1944, Chambers addressed Rand’s various points in some detail, showing how seriously they were taken at Bobbs-Merrill. He concluded his letter by assuring Rand that “The Fountainhead has at all times had the devoted interest, the wholehearted support of our entire organization. It deserved it.”

To Alan Collins (February 15, 1946)

Alan Collins (1904–68) was Rand’s literary agent at Curtis Brown Ltd. from 1943 until his death in 1968. That agency still handles her books. The letter below was in response to Collins’s letter of February 1, 1946, in which he conveyed the offer of Denver Lindley that “if he liked the new book [Atlas Shrugged], they [Appleton-Century] would be willing to put up an advance of $75,000 and a guarantee of somewhere between $25,000 and $50,000 for advertising.”

Dear Alan:

I am very much impressed by Denver Lindley’s offer and shall keep it in mind. However, it’s entirely premature. I have not started the writing of my next novel and won’t be able to start until I finish my six months at the studio. I merely have the outline of the novel ready in my mind. Wonder where Lindley got the idea that it was nearly finished.

I shall think of this offer whenever I feel like getting conceited about my own value. In the meantime, I’m glad that the novel has already earned two cocktails for you. Drink to it once in a while — I’ll need it.

Sincerely,

To Ann Watkins (March 29, 1946)

Ann Watkins (1886–1967) was Rand’s literary agent beginning in 1935, although by the time of this letter, Alan Collins of Curtis Brown Ltd. was taking over most of Rand’s works. The Watkins agency still exists under the name Watkins/Loomis. Anthem was first published in 1938, by Cassell in the United Kingdom. The first American edition, a significant revision of the Cassell edition, is the one discussed in the letter below; it first appeared as the Vol. III, no. 1, issue of The Freeman. The Pamphleteers edition was taken over by Caxton Printers in 1953 and then by New American Library in 1961.

Dear Ann:

I have made a deal to have ANTHEM published as a pamphlet by Pamphleteers, Inc., an organization which publishes political booklets and which is run by some prominent California men who are friends of mine.

They sell their publications mainly through private orders and mailing lists — but they will also sell to bookstores, if they get requests for it. I have found out from a lawyer that I can take out a copyright on a revised version of ANTHEM. This will not stop anyone from using the original version as public domain, but it will protect the new version and will serve as a sort of “psychological” protection for the old one.

I am doing this in order to have ANTHEM issued in proper form in America — rather than have it suddenly appear in a pulp magazine. After that, if anyone still wants to print it without permission, it won’t be quite so bad.

Will you draw up a contract for this deal and mail it to me? I will get it signed and send a copy back to you. I presume we will need three copies made.

The name of the organization is: PAMPHLETEERS, INC., 725 Venice Boulevard, Los Angeles 15, California.

The terms on which we agreed are as follows:

I grant them the right to publish a revised version of ANTHEM in booklet form.

If there are any second serial rights, such as requests from magazines for reprints, as a result of this publication, the money derived from such rights is to be divided equally between Pamphleteers, Inc. and me. The sale of such second serial rights is entirely up to me. They cannot authorize reprints without my consent.

All other rights are reserved to and by me.

Pamphleteers, Inc. are to pay me ten percent (10%) of all their gross receipts from the sale of this booklet, after the first 5,000 copies.

No changes of any kind whatsoever are to be made in the text of the booklet without my consent.

The copyright is to be taken out in their name (but to be owned by me — in the same manner as when a regular publisher takes out a copyright on a book in his own name.)

All advertising copy which they use for the booklet must have my approval.

(The first 5,000 copies are to be royalty free, because a great part of this number is given away free and the organization gets no profit until after this figure. My royalties are to be computed, not on the retail price of the booklet, but on their gross receipts, because their selling price varies according to the size of the order. We have not discussed the dates when they are to give me an accounting — I suppose it should be twice a year, as with regular publishers. They will send the accounting and the checks to you.)

These are the terms we have agreed upon. I’d like you to draw it up into a regular contract stated in proper legal terms. If there are any points which we have overlooked and which should be covered in the contract, please include them in the same way and on the same terms as they are in a contract with a regular publisher. Please let me know if there is any other important condition which I should discuss with them and include in the contract.

I am now revising the copy — and they will go into print as soon as I am ready. I would appreciate it very much if you would send me these contracts as soon as conveniently possible.

What is happening with Famous Fantastic Mysteries?4 We don’t, of course, have to inform them about this deal. I’d like to beat them to the publication, if possible.

With best regards,

Sincerely,

To Ruth Meilandt (July 11, 1946)

Ruth Meilandt, a manager at the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, was one of the six “Pamphleteers” (who included Leonard Read) who comprised Pamphleteers, Inc., and handled much of the organization’s business matters.

Dear Miss Meilandt:

Thank you for the sketches of covers for ANTHEM, which you sent me.

The cover I have selected is sketch #6, but with an adaptation of my own which I am enclosing. I think #6 is the best for design, but I object very strongly to the drawing of the Grecian torch; it is much too conventional. What I would like to see in its place is the drawing of a flame, as I have indicated on my attempted version. To get the effect I have in mind (which would be excellent for the story and in keeping with it), I would like it to be the drawing of a stylized wind-blown flame — not a realistic conventional one. If the artist can do that, I think it would be very good. Also, I would urge very strongly that the oval be a single line, not too heavy, and that the letters of that title be drawn sharp and straight, not rounded as the artist has suggested. This makes the appearance of the jacket much stronger.

I do not care for sketch #5, because it is too crowded, because the odd lettering of the word ANTHEM makes it illegible at first glance, and because the torch is too conventional.

In order to have the cover right and not regret it afterwards, I would like very much to see the artist’s sketch of my suggestion before a cut is made from it. I will return it to you promptly.

I would also like to see a proof of the little advertising leaflet which Mr. Ingebretsen sent me.

As to the inquiry you received about purchasing a copy of WE THE LIVING, please tell the gentleman that the book is out of print now, and he can get a copy only by advertising for a second-hand one; or he may still find it in the public library.

Sincerely,

Meilandt responded two days later that Rand would shortly receive a revised sketch. The published edition replaced the drawing of the Grecian torch with a flame, as Rand recommended.

To Ruth Meilandt (August 5, 1946)

Dear Miss Meilandt:

I am sorry if I seem to be giving you difficulties, but since you wanted the cover of ANTHEM to please me, I must tell you my true opinion, which is: that the change in lettering has practically ruined the appearance of the cover. It has thrown it out of balance, and the narrow lettering does not stand out as the original lettering on the drawing would have.

If changing this now will involve too much trouble and delay, I suppose you will have to let it go as it is. If it is still possible to change it, I would like you to have the lines within the oval hand-lettered in the kind of bold letters you had before. Since we have spent this much time on the cover, I would like very much to have it right and not to spoil it by a detail of this nature. Please charge the cost of the alterations and of the new lettering to me. I will be glad to bear this cost, as I think it is worth it.

Sincerely,

On August 16, 1946, Meilandt responded that she will send Rand “a photostat of the finished sketch for your approval.” And on August 19, 1946, Rand replied that “the revised cover which you sent me . . . looks fine now, and I am looking forward to getting the finished copies of the book.”

Cover of Anthem by Ayn Rand

To Alan Collins (August 6, 1946)

This letter is part of extensive correspondence between Rand, Collins and Ross Baker (sales manager of Bobbs-Merrill’s trade book department) regarding royalties.

Dear Alan:

Thank you for your letters of July 24th. I am sorry that you did not corner Ross Baker with the only question I wanted answered, which was: why did they not consult me before they made sales in the open market?5 They have never answered this, and all the rest of their explanations are completely irrelevant.

At present they are making me lose the open market sales entirely, since they will not even negotiate about this market, and since they take the position that I must not only accept their arbitrary conditions, but also accept their right to have taken this market without permission. Unless I do so, I cannot have the book sold on the open market, and since I will not do so, they are now responsible for a direct financial loss to me, through a method of doing business which comes awfully close to blackmail or high pressure. I will leave it up to you as to whether you will permit this to go on or not. I should think that this much can be settled without going to court. As for the rest, I will consult an attorney about it.

I may come to New York later this fall and settle this in person, but I do wish you could save me some of the trouble.

As to IDEAL, I was shocked to hear that you had submitted it to Shumlin.6 I am sorry that I did not warn you against doing this. Please make it a matter of irrevocable policy in the future not to send any work of mine to any producer or publisher known as a Communist. Do not send IDEAL to any producer who has an established pink reputation, such as the following: Oscar Serlin, Shepherd Traube, Orson Welles, the Playwrights’ Company or any left-overs of the Group Theatre. I do not know all of the current crop of red producers, but I will leave it up to your judgement to inquire about them and not to submit my play to those whom you find to be pink. Please be as careful about this as you possibly can. You must surely realize that those people will never produce anything of mine — nor would I let them produce it.

Sincerely yours,

On August 14, 1946, Collins responded that he thought Bobbs-Merrill “were doing you a good turn by selling” in the open market. He also told Rand that he had sent the script of “Ideal” to Shumlin “with tongue in cheek, for I wanted to see, in the light of his political prejudice, what his reaction to such a forthright script would be. Unfortunately, he sent it back without comment.”

To Gerald Loeb (July 31, 1947)

Gerald Loeb (1899–1974) was a founding partner of the stock brokerage firm E.F. Hutton & Co. Rand and Loeb had a lengthy correspondence between 1943 and 1949, during which period her daily calendars list numerous meetings and dinners with him.

Dear Gerald:

Thank you very much for your many notes and letters to which I owe you an answer. I am late as usual, but you know me by now and you will forgive me.

First, I want to tell you how much I enjoyed your last visit here and meeting Rose. I am glad you wrote that she likes me, because I liked her very much and I think you will be very happy together. All my best wishes again for both of you.

I had a very nice letter from your mother in which she mentioned that you were to send us the photographs which she took of us here. This is just a reminder to tell you that we would like very much to have them.

I was interested to see the little pamphlet by Mr. E. F. Hutton and his ad in the New York Herald Tribune. The ad particularly is excellent. Mr. Hutton is obviously sincere about the fight, and I should like to meet him when I come to New York or if he over comes to the West Coast.7 I am glad you sent him a copy of ANTHEM. Let me know what he thought of it. Do you think I should send him some copies of my articles on Americanism in THE VIGIL, the Motion Picture Alliance magazine? I believe they could be helpful to him.

Now as to the letter from Miss Jean Dalrymple,8 even though she paid some nice compliments to my writing, I wish you had not sent the letter to me, because it is a rather offensive letter, though I am sure she did not intend it as that. She says that she “certainly could be of assistance in having Miss Rand turn out a tremendous theater work.” Gerald, darling, you surely know me well enough by now to know that I do not write with anybody’s assistance. When and if I decide that I want to write a new play, I will write it. I have never undertaken a piece of writing on somebody’s suggestion, advice or prodding. When I come to New York I would be glad to meet Miss Dalrymple, but only on condition that she give up any idea of moulding me like some writer from P M.9

I have no special news about myself, except that I am working on my new novel, am enjoying it tremendously and it is going very well. I don’t know as yet when I will have it finished, but I know that I will not be able to come to New York this fall. So I am looking forward to seeing you and Rose here when you come west.

Best regards from both of us to both of you,

Sincerely,

To John L. B. Williams (December 13, 1947)

John L. B. Williams (1892–1972) was an editor at Bobbs-Merrill.

Dear Mr. Williams:

Thank you ever so much for the copy of WE THE LIVING which you obtained for me. I was delighted to get it. I am enclosing my check for it. If you find that you can get any additional copies, I will be happy to have them.10

I will not attempt to tell you what a wonderful time I had riding in the engine of the Twentieth Century. It was the greatest experience I ever had.11 I guess I will save the description of it for my novel. I am back at work on it, and it is going well.

Thank you for the nice luncheons we had in New York. I am looking forward already to my next trip there.

With best regards,

Sincerely,

To Pincus Berner (April 3, 1948)

Pincus Berner (1899–1961) was Ayn Rand’s attorney, beginning with an arbitration in 1935 against producer Al Woods regarding Night of January 16th. The subject of the letter below is what Rand termed the “Banyai Case.” Shortly after the end of World War II, George and Tommy Banyai, without Rand’s permission, put on a French production of Night of January 16th. The lengthy dispute over royalties had already been going on for more than two years at the time of this letter to Pincus Berner. In 1949, Rand eventually sued George Banyai to recoup royalties. Rand and Berner caught him in various lies and trickery (Rand congratulated Berner “on the skill with which you pinned down the wriggling little liar”), but Banyai actually expanded productions of the play throughout Europe even while being sued for not paying royalties.

Dear Pinkie:

Thank you for your letter of March 18.

I thought I had made it clear that I would not join the French Society of Authors under any circumstances whatever. So please let us omit this from our considerations of the case.

Do you not find a peculiar discrepancy in Banyai’s attitude? You say in your letter, “I can see no point in suing Banyai in a local court. We have no figures on which to predicate the sum due you from him.” You also state that Banyai reported that the French Society has refused to give any statement or computation of the royalties accruing to me to date. Does Banyai mean to imply that he or his brother have no copies of their accounts or bookkeeping statements and no record of how much money they deposited with the French Society in my name? Why did he have to ask the Society for that account? The Society does not owe it to me — he does. Do you propose that we let him get away with that? I think you should demand, not ask, but demand an accounting from him at once.

Besides, I sent you a copy of the letter from Tommy Banyai of January 15, 1948, in which he states that the amount of my royalties at present is approximately 500,000 francs.

As you know, there is a clause in my contract with George Banyai which states that any differences arising between us are to be settled according to the laws of American courts. Therefore, I believe it would be a mistake for me to give Banyai permission to sue the French Society in my name. Such an action would amount to waiving my claim against Banyai and recognizing the jurisdiction of the French Society in this matter, which I do not recognize. My contract is with George Banyai, and my claim is against him. If he says that under French laws he is helpless against the French Society — my stand is that that is his problem, not mine, because our contract states specifically that I am not bound by French laws. Therefore, I think I must undertake a suit against him right now and in New York. It seems to me that the suit should be not merely for royalties, but for breach of contract and bad faith, and that the first demand we must take on him is to subpoena from him an accounting of the sums due me.

George Banyai has a great many activities and business connections in this country, so I believe we could attach whatever he owns or part of his salary to satisfy a judgment against him. It is my impression that he would not let matters go that far and that he would find a way to settle my claim. I don’t believe I mentioned to you that he was the representative of the French Society of Authors in Hollywood, so you can see what the situation really is.

I am not sure of the exact value of the franc by the rate that prevailed at the time my royalties became due; but as far as I can guess, the amount they owe me is probably somewhere between four and five thousand dollars. This is a sum which I believe can be collected from George Banyai in person right here.

On the grounds stated above, I would like you to institute a suit against George Banyai in New York and to ask for damages. Please let me know whether this can be done, what it involves and what would be the exact procedure to follow. Also please let me know whether you will undertake to handle it on a contingency basis or, if not, please tell me the exact sum you would charge me for handling this. You can realize why I cannot undertake this without advance knowledge of how much it will cost me.

With best regards,

Sincerely,

The outcome of Rand’s fight with the Banyais is not known. Papers in the Ayn Rand Archives indicate that Banyai did send some back royalties to Rand, but the last mention of the lawsuit is in an August 31, 1949, letter to Berner in which she implies that a motion for summary judgment was unsuccessful. Then, in the 1950s, Rand refers to Banyai’s “fraud” regarding Scandinavian rights to the play and says that his actions were “more nefarious — if that is possible” than in the French “affair.”

To Rosemary York (September 4, 1948)

Dear Mrs. York:

Thank you for your letter of August 23rd.

I am enclosing the tipsheet which I have inscribed for Mrs. Bett Anderson.

Please tell Mrs. Anderson for me that I was delighted to hear of her request, and I am complying with real pleasure. I do remember her review of THE FOUNTAINHEAD very well indeed. It was one of the only two reviews which I really liked — the other one was Miss Lorine Pruette’s review in the NEW YORK SUNDAY TIMES. At a time when so much senseless drivel was being written about THE FOUNTAINHEAD by the majority of the reviewers, these two gave me hope that some real intelligence still existed in the world. I shall always be profoundly grateful to Mrs. Anderson for that.12

The motion picture of my book is coming along beautifully, and if all goes as well as it has, I have reason to hope that it will be a great picture.

With best regards,

Sincerely,

To Jeannie Cornuelle (April 19, 1980)

Jean Cornuelle and her family were friends of Ayn Rand and Frank O’Connor. Rand’s correspondence, primarily with Jean’s husband, Herb, began in 1950. Herb, whose business career included presidencies of Dole Pineapple and United Fruit Company, was one of the founders of the Foundation for Economic Education.

Dear Jeannie,

I was delighted to hear from you — but the reason that I did not answer you sooner is the improper request that your friend, Mr. Danks,13 has imposed on you.

Mr. Danks has committed an illegal action in trying to adapt my book, Anthem. It is legally forbidden to adapt an author’s work without his/her prior permission. I categorically refuse to give such permission to Mr. Danks. I have not read his script, and I am returning it to you under separate cover.

The reason for my disapproval of Mr. Danks is that I cannot stand the thought of someone monkeying around with my material. My work means too much to me. If you remember the climax of The Fountainhead, I am sure you will understand this.

I am sorry that he has attempted to use you in such a manner — and I certainly do not hold it against you, only against Mr. Danks.

I was glad to hear about your family, although I cannot imagine you as a grandmother. I will always think of you as Dagny Taggart.

I am sorry to have to tell you that Frank died last November after a long illness.

I was glad to hear that there are “young Randians” in Hawaii. But you make a mistake in associating the Libertarians with me. They are my enemies and have nothing to do with my philosophy, except for occasional attempts to plagiarize it.

If you ever come to New York, please let me know. I would love to see you again.

With love to you and Herb — and do svidanie.14

Endnotes

- A few typographical errors and outmoded typewriting styles in these letters have been corrected without notation.

- Omnibook Magazine was a monthly publication containing “authorized” abridgements of novels and was geared especially to members of the armed services. An abridgement of The Fountainhead was published in the January 1944 issue.

- The Reader’s Digest article to which Rand refers is likely “The Only Path to Tomorrow” (originally titled “The Individualist Credo”), published in the magazine’s January 1944 issue. The text was to be subsumed under her book “The Moral Basis of Individualism,” which was contracted for by Bobbs-Merrill but never completed.

- Anthem was published in the June 1953 issue of Famous Fantastic Mysteries magazine.

- “Open market” sales refer to discounted sales via middlemen.

- Herman Shumlin (1898–1979) was a well-known producer of Broadway plays, including Inherit the Wind and four plays by Lillian Hellman. His obituary in the New York Times described him as “a passionate political liberal” with “a strong sense of social commitment.”

- Neither the pamphlet nor advertisement is in the Ayn Rand Archives, nor is there any evidence that Rand ever met Hutton.

- Jean Dalrymple (1902–98) was a theatrical producer and one of the founders of New York City Center, a theater where she produced revivals of major plays, including King Lear with Orson Welles.

- PM was a left-leaning daily newspaper published in New York City from 1940 to 1948.

- After Macmillan sold out the original printing in 1936, it destroyed the plates (in violation of its contract with Rand). The novel remained out of print in the United States for more than twenty years.

- For Rand’s description of this train ride, see Letters of Ayn Rand at pages 188–91.

- The full text of Anderson’s review can be read by following this link.

- Likely William Danks, a libertarian writer.

- In Russian, “do svidanie” means farewell, or goodbye until we meet again.